Since 7 October, Israel has ramped up efforts to drive Palestinian shepherding communities out of the northern Jordan Valley

This article was first published by Relief Web on 18th March 2024

Since the Hamas attack on Israel on 7 October 2023, Israel has stepped up its efforts to drive dozens of Palestinian shepherding communities in the northern Jordan Valley out of their homes and lands. Through cooperation and collaboration among the military, police, settlers and the Jordan Valley Regional Council, Israel has reduced grazing areas available to Palestinians, blocked regular water supply and took measures to isolate the Jordan Valley from the rest of the West Bank.

This policy is nothing new. Israel has been undermining these communities’ subsistence for decades, in part, by denying Palestinians’ access to nearly 80% of the Jordan Valley declared as firing zones, nature reserves or the municipal area of settlements. Israel uses these zoning declarations to justify its refusal to approve building plans that would allow residents of these pastoral communities to build homes legally and connect to water and electricity infrastructure. On top of this, with full backing and protection from the military and the police, settlers subject residents of these communities to severe violence on a daily basis. This policy imposes impossible living conditions on Palestinian residents of the Jordan Valley.

It has been ramped up since 7 October, with pressure exerted in several ways:

Land takeover

Towards the end of the previous decade, six settler farms were established in the Jordan Valley: Shirat Ha’Asavim, Tene Yarok, Maskiyyot, Eretz HaShemesh, Nof Gilad and Goshen. The settlers living on these farms, consisting of several families and a few dozen youths each, raise cattle and sheep, and they are the main source of pressure on Palestinian pastoral communities in the area.

Even before the war, these settler-farmers seized control of about 57,500 dunams (1 dunam = 1,000 sq. meters) – an area larger than the municipal boundaries of Israel’s largest city, Tel Aviv. Most of this area lies between Route 90, Jordan Vally Route, and Route 578, Alon Route. Settlers have also taken over two freshwater springs used by local Palestinian communities, one near ‘Ein al-Hilweh and one near the al-Farisiyah community cluster, as well as rainwater cisterns these communities dug and used for watering livestock.

Since 7 October, the settlers have taken over an additional 4,000 dunams and fenced off the areas they took over before the war. They also set up roadblocks to deny Palestinians access to agricultural roads they used in the past. The settlers installed fences along two sections of Route 90, near the settler farms of Nof Gilad and Goshen. More fences were put up across from the al-Farisiyah community cluster, east of Route 578; near the Eretz HaShemesh settler farm; on an agricultural road leading from Route 90 to the Goshen settler farm, and on the agricultural road between the settlements of Maskiyyot and Rotem.

These settler farms now control a vast area that Palestinian pastoral communities have been using as pastureland for decades, both before and after the occupation of the West Bank in 1967. Parts of this sprawling area were declared a firing zone or nature reserve by Israel sometime between the late 1960s and 1980s, and with the proliferation of settler farms, it is now effectively completely closed to Palestinian shepherds and cowherds whose livelihoods have been jeopardized as a result.

Settler violence

Attacks by residents of settler farms have long since become part of daily life for the Palestinian communities in the area. Testimonies collected by B’Tselem and evidence recorded by Israeli protective presence activists who work with these communities show these attacks have grown more violent and more frequent since 7 October.

The violence includes speeding erratically directly into Palestinian flocks and herds on ATVs or horseback, running over livestock, grazing settler livestock in cultivated Palestinian fields and damaging crops, setting dogs on Palestinian residents, raiding communities by night, stealing livestock, vandalizing property, setting property on fire, physically assaulting Palestinian residents and Israeli protective presence activists and repeatedly threatening community members not to go out to pasture. The Israel Police largely refrains from investigating these incidents, and when Palestinians or Israeli activists file complaints with the police, they often find themselves interrogated as suspects.

Travel restrictions

In the late 1990s, the military installed two checkpoints in the Jordan Valley on the roads leading from Tammun and Tubas Districts to the northern Jordan Valley – Hamra and Tayasir. In recent years, Palestinians have been allowed to cross them freely, but since 7 October, the checkpoints have been staffed again and the soldiers stationed in them carry out lengthy checks of Palestinians who are not registered as Jordan Valley residents, including teachers and physicians working in the area and Palestinians traveling to Allenby Bridge en route to Jordan. These checkpoints also impede water deliveries to pastoral communities in the Jordan Valley, which depend on these deliveries as Israel refuses to connect them to the water grid. Ever since 7 October, these checkpoints have been the scene of long car queues, with waiting times of up to two hours.

Another Jordan Valley checkpoint, Gochia, west of the settlements of Beka’ot and Ro’i, is used to run checks on Palestinian laborers working in settlements and restrict Palestinian travel, including tankers that pump water near Khirbet ‘Atuf and deliver it to local communities. Since 7 October, the military has reduced the checkpoint’s hours of operation and it currently opens only three times a day, for short durations, and subject to frequent changes.

Soldier violence

After 7 October, local settlers were recruited into the military’s regional defense program in the area. They now act as a security detail for fellow settlers, including when they attack Palestinians, and often take part in such attacks themselves. In their role within the military system, these individuals work in tandem with fellow settlers to reduce Palestinian communities’ access to pasturelands, including by arresting and detaining Palestinian farmers and confiscating tractors they use to plow near areas declared as firing zones and nature reserves.

The military is also fixing the dirt embankment along Route 578 – from Beka’ot to the Gochia checkpoint, originally built during the second Intifada to block Palestinian farmers’ access to their fields west of the road. In recent years, Palestinians could reach their lands through gaps that formed in the embankment.

Harassment by the regional council

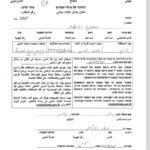

Ever since 7 October, the Jordan Valley Regional Council has adopted the practice of confiscating livestock belonging to Palestinians, claiming they are “stray animals” or invoking the council’s grazing bylaw. The confiscations are carried out in collaboration with settler farm residents, the military and the police. So far, the regional council has confiscated two Palestinian cattle herds numbering more than 200 animals and demanded farmers pay about 200,000 NIS (~ USD 55,600) for transport and upkeep.

The first incident took place on 24 December 2023, when council workers confiscated a herd of cattle belonging to cowherds from the community of ‘Ein al-Hilweh near the settlement of Hemdat. The second confiscation took place on 7 January 2024. According to a court petition filed by cowherd families from ‘Ein al-Hilweh, settlers from the Nof Gilad settler farm invited them to graze their cattle near the settlement of Brosh Habik’a, but when they arrived, regional council enforcement officers, who were waiting for them, confiscated 48 cows and arrested the cowherds with the help of soldiers and police.

Responding to a letter Adv. Michael Sfard sent on behalf of the cowherds, the military’s Legal Advisor for the West Bank, Col. Eli Levertov, clarified that the council took these actions despite having no enforcement powers regarding Palestinian communities in the area. The Legal Advisor also stated the council’s actions ran counter to the position of his office and defied High Court rulings.

In another measure affecting grazing access, the regional council allocated a vast area of about 6,200 dunams to the Tene Yarok settler farm, which belongs to Didi Amosi, formerly the civilian security chief for the settlement of Rotem. This allocation increased the farm’s pastureland to 16 times the size of the original 370 dunam-allocation by the Ministry of Agriculture in 2021, and it prevents the nearby communities of al-Farisiyah from grazing their livestock east of Route 578, up to Route 90, as they have had done for decades.

Each of the Palestinian communities in the Jordan Valley owns hundreds of sheep and cattle. As access to pasturelands decreases, they are forced to purchase animal feed, the cost of which has grown dramatically over the past two years due to the war in Ukraine. Blocked access to water sources means dependency on delivered water, which is pricier the more remote the community, because of transport difficulties. These challenges hinder these communities’ ability to sustain animal husbandry as it becomes financially unfeasible.

Israel’s pressure is designed to destabilize the economic foundation of these Palestinian pastoral communities and push the Palestinian population out of the Jordan Valley, with the ultimate goal of perpetuating the apartheid regime in this geographical area and freeing Israel to use the land for its own interests.

In testimonies given to B’Tselem field researcher ‘Aref Daraghmeh, Palestinians in the northern Jordan Valley described how the settler takeover of land and water sources and the authorities’ conduct has cost them their income:

Testimony of Qadri Daraghmeh, 75, a father of five from Khirbet ‘Ein al-Hilweh:

My brothers and I have more than 400 heads of cattle in the area. We used to graze our herds over vast areas covering thousands of dunams (1 dunam = 0.1 hectare). In recent years, our space has gradually shrunk and our lives have become difficult and restricted. We are hemmed in on all sides because the settlements, settler farms and the military have taken over a lot of land around us. Taking the herds out to pasture is frightening nowadays. Every day, the settlers chase us and attack our children. They also brought herds of cattle and started grazing them in places where our cows and sheep grazed for years.

Even so, what we went through on 25 December 2023 was exceptional. My sons, ‘Udai and Muhammad, were grazing our herd near Um al-‘Ubur and Marj Na’jah, west of Route 90. They told me that people from the the regional settlement council attacked them. I went there with my brothers, whose sons were also grazing herds in that area. I saw settlers, people from the council, soldiers and police leading our cattle towards the settlement of Hemdat, based on the claim that we were grazing them in areas we are forbidden to enter and areas by the road. After that, they brought in trucks and loaded our herd onto them.

A fight broke out and instead of giving our cattle back, the soldiers detained my sons for several hours. We had more than 100 heads of cattle in that herd. They held it for days, and then claimed they had a lot fewer than the number taken from us. After we asked lawyers and activists for help, we got a notice from the council saying we had to pay a fine of 49,000 shekels (~13,700 USD) to get back 19 heads of cattle. But the herd they took away was much larger. I borrowed the money and paid up, and they gave me 19 heads of cattle back.

On the evening of 7 January 2024, a herd that I own with my brothers was grazing in the same place, far from the settlers and the area of Route 90, and settlers and people from the council attacked shepherds from my family again. They called us, and when we arrived, about 10 settlers started throwing stones and chasing us. They took part of Adel’s herd, attacked me with sticks and kicked me. I fell down and they continued beating me. I was taken to a hospital in Tubas, and thankfully wasn’t seriously injured. The settlers also attacked my sons, who were in a car. They smashed the car windows, but the military arrested them anyway, and is still holding them. I’m very worried about them.

The settlers want to get rid of us and annex the entire area to the settlements. They don’t want us here, and because of them we’re living as if we’re under curfew. We’re afraid to venture further away to places where there’s a bit of pasture for our cattle. They’ve offered many times to buy our cattle off us, and we’ve refused.

Testimony of ‘Abd a-Rahman Khalil, 70, a father of ten from Khirbet al-Maleh:

My family and I have been living in the al-Maleh area for decades, but since the occupation began, all our possibilities our gradually closing in on us. We’re living in constant lack, under ongoing persecution. Year after year, the settlers grab more and more of our land. They set up farms here and brought cattle and sheep to graze on our land. But since the end of 2023, things have got worse. The settlers started breaking into our tents and taking over land very close by. In the past month, they’ve come here more than seven times. Just five days ago, I took my sheep as usual to the area south of our tents, where I always used to graze them. When I got there, the settlers’ cows were already there. The settlers forced me to leave, and I had to go back to our tents. I often have to stay home and leave the sheep in their enclosures because we have nowhere to graze them. That means having to buy feed for them. We’re already more than 50,000 shekels (~14,000 USD) in debt for feed. It’s the same for dozens of families in the area.

I used to have more than 40 cows, but I sold them at the beginning of the year because there’s nowhere left to graze them. With half the amount I got for them, I bought feed and medicine for my sheep, just so I can continue living like this, even though this lives has become hell for shepherds. We used to rent plots every year to grow crops for the family and for the sheep. But the settlers set up a farm next to the land, and today you’re risking your life if you go there, because of the settlers and because the army confiscates your tractor if you try to work the land there. The army and the police stand by them.

I don’t know what to do. If I sell my sheep, too, what will I work at and how will I provide for my family? I’m old and tired. May God help me with what I have left in my life. Now, all the shepherds say that we should save ourselves and find other work. There’s no place left for us to graze livestock here, and there’s barely anywhere to live. The settlers take over more land every day. They’re armed and all the authorities support them. We have no way to fight them.

Testimony of Yusef Bsharat, 47, a father of seven from Khallet Makhul:

I’m a shepherd and have more than 400 sheep. It’s my main work and that of my family. It’s the only work we know how to do, and we have no other source of income. When we had pastureland, before the settlers closed off the area, we made a good living and even managed to save money.

Now we have to buy feed on credit to continue our way of life. Also, because the Israeli water company refuse to connect us to the water network, we have to waste precious time and money to get water in containers. In the past, I would travel at least twice a day the area of Ras al-Ahmar to fill up three cubic meters of water in a trailer tank for my family and sheep. I was always afraid of the police and the army, who made up excuses to prevent us from getting the water. But since October 2023, the army closed the gate (Gochya checkpoint) they set up on the road leading to the water source. Today, I need to waste a full day’s work to get three cubic meters. So I have to buy water from a tanker every three days, and it costs me about 200 shekels for 10 cubic meters. The tanker is not always available when we need it, and we have to wait hours for it to arrive because of the checkpoints. The Mekorot pipeline passes right through our land, right next to our tents, while in the summer when it’s hot we barely have any water. My children can only hear the water flowing in the pipes and touch it to feel the coolness. We’re not even allowed to access our cisterns for collecting rainwater. The settlers have taken control of them and use them for their cows and sheep. If they could, they would deny us the rain itself.

The occupation does everything to limit our ability to live here. They deny us access to water and lands in order to drive us away. They’ve already demolished our tents, confiscated our tractors and prevented us from plowing the land. We’re now living in a prison. Everything is blocked for us.

Testimony of ‘Abed Abu ‘Awad from Khirbet ‘Ein al-Hilweh, 49:

My father and I have about 1,000 sheep and goats that need large quantities of water. I bought a tanker to get water for the livestock and for my family, and until recently I would travel once a day, or even more in the summer, to the area of Khirbet ‘Atuf or ‘Ein Shibli to fetch water. Every trip with the tanker cost me between 100 to 150 shekels. But in early October 2023, after what happened, the occupation soldiers set up a checkpoint in the ‘Atuf area (Gochya checkpoint). Now, the army requires coordination and entry and exit permits for the tanker. Since then, my tanker has been standing, unused, in Ras al-Ahmar.

Now I’m forced to order water from a tanker belonging to someone from Tubas. He comes to me every three days and provides me with 10 cubic meters of water, at a price of about 200 shekels. In the last two months, I’ve ordered water from him 17 times. We make sure not to waste a single drop, we can’t afford to. It is so difficult and expensive to get it. I pay more than 70,000 shekels (~USD 19,000) a year for water and its transportation. If we could use wells or cisterns to store rainwater, it would cost less than a third of that.

In the past, we used rainwater cisterns we leased from their owners, and that saved us some expenses. But the settlers took control of them, too. They use the collected rainwater for their cows and sheep. Mekorot laid down a new water pipe that runs past our tents, but they don’t allow us access to that water, not even fill a cup with it.

The occupation has taken everything from us. The settlers established a farm east of where we live and brought cows there. Within two or three days, they already had the water network connected directly to their pens. People here are living in growing hardship. The occupation, the settlers and the authorities do not want us to stay here. They think: “We’ve prevented their access to pastureland, and now it’s time to prevent their water supply, too.” Then we’ll have no choice but to sell our sheep and leave this place. That scenario is a disaster for us, because we have no life without our sheep.

Testimony of Fawzi Dagharmeh from Khirbet Samra, a married father of six:

I raise sheep. I inherited that work from generations that came before me. My family owns more than 1,000 heads of sheep. We live on the outskirts of our family’s village, in tents and tin structures, surrounded by military bases and settlements. They don’t allow us to live with dignity, and we are forbidden to build anything. We’re not even allowed to sleep peacefully at night. The occupation doesn’t want us to stay here. The pastureland we used, which were our only refuge, have been closed off in favor of the settlement outposts built around us.

In Khirbet Samra, there are no water sources. We are not allowed to use the cisterns where we used to collect rainwater, and they don’t allow us to fix them. The settlers also took over wells located north of Khirbet Samra. The authorities also prevent us from connecting to the water network in the area. I have to travel several times a day to get about three cubic meters of water each time, and every trip costs me 50 shekels. Since the war in Gaza, soldiers closed the gate (Gochya checkpoint) leading to the place where we used to fill up water in Ras al-Ahmar, and they open it at irregular hours. I cane lose a whole day of work just getting there. Sometimes we buy water from the tanker of relative, who brings us 10 cubic meters of water for 200 shekels every time. But it’s not always available, and sometimes I have to order water from the owner of a large tanker, which is more expensive.

In summer, we need about 10 cubic meters of water a day, but in winter, that amount is enough for us for three days, both for the sheep and for the family’s needs. We spend more than 60,000 shekels (~USD 16,300) a year on water, for us and our sheep. These prices prevent us from many other things in life, and we also run up debts for water and animal feed. If the pastureland and access to water sources weren’t blocked for us, we wouldn’t be in debt.

Testimony of Nabil Dagharmeh from of Um al-Jamal, 51, a married father of seven:

*We used to live in ‘Ein al-Hilweh. The settlement of Maskiyyot was established opposite us. But the occupation forces destroyed our tents, and we were forced to move to Um al-Jamal. Now they’ve informed us they intend to demolish our simple tents here, as well. We make a living from raising sheep. But the last few years have been tough because the settlers established farms, bringing cows and sheep to graze in the areas where we used to graze our sheep. They chase us everywhere, and they also attacked my sons when they were in pastureland, beat them and injured them.

One of the things we suffer from most is the shortage of water. The only source left for us to water our sheep is a spring near Um al-Jamal, more than 2 kilometers away from our community, which has only a small amount of water not suitable for human consumption. The settlers, who already took over the ‘Ein al-Hilweh spring, have recently started going to that spring as well and stopping us from using the water.

I am forced to buy water from a 10 cubic meter tank for 200 shekels. I pay more than 10,000 shekels (~USD 2,700) a year for water for my family and our sheep. The water pipe of the Israeli Mekorot company passes less than 50 meters from my tents, but they don’t allow access to this water.

If it weren’t for my family in Tubas, believe me, I wouldn’t be able to pay for water. Every year, I go with the sheep to the Tubas plain, because there are more water sources there. That way I can provide for the basic needs of my family, save some money and buy water. To cover my debts for water, I had to sell some of the sheep. We are constantly making efforts to get water because without it, we cannot survive or raise the flock.

Testimony of Luai Abu Muhsen from al-Farisiyah, 42:

I live in al-Farisiyah near Naba’ Ghazal with my father’s and brother’s families, and we all raise sheep. Over the years, especially in the last two years, we’ve suffered greatly from the occupation, the settlers and the settler council. They often harassed us, prevented us from accessing pasture and beat us. They confiscated our tractor twice for long periods, and demanded a lot of money to get it back. In the past three months, our suffering has intensified. Every day the settlers harass, chase and attack us, often with the support and assistance of the occupation army.

On the morning of 17 December 2023, I headed east with my brother Barakat and the flock, east of where we live, to the area that’s furthest away from the settlement of Rotem. We felt that the day wouldn’t pass peacefully, because the settlement security guard and his son were patrolling the area and monitoring us. Around 11:30 A.M., we were surprised by a pickup truck that sped towards us and ran over two sheep. The flock scattered. Someone got out of the truck, and we recognized him as a settler from Rotem. He shouted at us and chased the sheep. He hit my brother Barakat on the leg with a sharp object, and caused a deep wound. We called the Israeli activists (for defense). They quickly arrived with members of my family, but the settler had already left. My brother was still in pain, and the sheep were in a kind of frenzy, running around uncontrollably.

The Israelis contacted the police and the army, who came to the area. We took my brother to Tubas Hospital and thankfully, he is okay. The police and soldiers stayed there for hours but did nothing. They collaborate with the settlers to persecute us.

How can we protect ourselves from the settlers and their attacks? They have blocked off all the areas and surrounded them with fences on all sides. All these areas were open to us and spared us the need to buy animal feed. The settlers are the ones who call the shots in the Jordan Valley now, and we have no one to complain to. All the institutions of the occupation work for them. A week before the attack, they plowed our land right next to our tents, and attacked one of the Israeli activists and threw a stone at his head. They don’t want anyone to support us or film their violent acts.

The damage they cause us is growing every day. They patrol the area, raid our tents and provoke us in order to harm us. Our neighbor, who is also a relative of ours, left the area because of their threats and moved further away to areas in al-Aqabeh in order to protect his family, even though he’s lived here for decades and the land belongs to his family. Other families have also left due to the threats from the settlers and their violence. We’ve corresponded with all the relevant authorities and DCOs, but they’ve done nothing. Israelis have been sleeping in our community for two months to protect us, and sometimes they accompany us to pasture. Otherwise, the settlers would burn our tents down on top of us.