Servicing the settlements

Better Place is an electric vehicle service provider now servicing settlers’ electric cars with battery switch stations. This year they have opened two new stations in the Jordan Valley. One in Tomer settlement, near the Palestinian villages of Fasay’il, and the other by Qalya settlement near to Megilot Dead Sea Regional Council, a settler run body in the south of the Jordan Valley.

Better Place is an electric vehicle service provider now servicing settlers’ electric cars with battery switch stations. This year they have opened two new stations in the Jordan Valley. One in Tomer settlement, near the Palestinian villages of Fasay’il, and the other by Qalya settlement near to Megilot Dead Sea Regional Council, a settler run body in the south of the Jordan Valley.

According to the company’s website, Better Place was conceptualised by Shai Agassi in 2005, following the World Economic Forum, to ‘make the world a better place.’ Marketing itself as a ‘forward-thinking’ enterprise committed “to break the world’s dependence on oil” by reducing CO2 car emissions, the company “believe[s] that endless opportunities exist for those who are brave enough to reinvent the way the world works.”1

Yet, evidently, the company’s ‘concerns’ to ‘make the world a better place’ are predictably and inherently improbable and contradictory. Disguising the company’s partaking in social injustices and lacking evidence of environmentally sound practices throughout the entirety of their operations, the company’s PR machine perpetuates not only ‘green-washing’ but by servicing settlements in the Jordan Valley, Better Place is profiting from and sustaining the occupation of the Palestinian Territories.

“We must boycott the occupation and everything that is linked to the occupation, be it directly or indirectly, and to boycott all those who profit from the occupation. Those that profit from the occupation, they are more dangerous that the occupation itself”, says Fathy Khdirat of Jordan Valley Solidarity.

Actualising apartheid

The battery switch stations near Tomer and Qalya settlements in the Jordan Valley are now operating to service settlers’ electric cars, contributing to settlement development and expansion by normalising the presence of the settlements and the needs of settlers. Even if electric vehicles were available to Palestinians in the Jordan Valley, they would not be allowed to access the station. At the same time, Palestinians in the Jordan Valley are prevented from developing the area, including building petrol stations, and are denied access to basic services and are faced with daily harassment and discrimination with the aim of cleansing the Jordan Valley of Palestinian communities.

The battery switch stations near Tomer and Qalya settlements in the Jordan Valley are now operating to service settlers’ electric cars, contributing to settlement development and expansion by normalising the presence of the settlements and the needs of settlers. Even if electric vehicles were available to Palestinians in the Jordan Valley, they would not be allowed to access the station. At the same time, Palestinians in the Jordan Valley are prevented from developing the area, including building petrol stations, and are denied access to basic services and are faced with daily harassment and discrimination with the aim of cleansing the Jordan Valley of Palestinian communities.

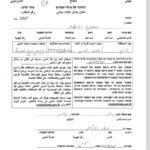

Palestinians in the Jordan Valley, under the occupation’s apartheid planning laws, are prevented from building their own infrastructure, including petrol stations. Yet, the Better Place battery switch station by Tomer settlement is easily accessible to settler’s cars traveling in both direction on Road 90, located just off the highway, highlighting the actualisation of apartheid roads and planning systems in the Jordan Valley. The power station demarcates the two clearly sign-posted entrances to Tomer settlement – only one hundred meters from the junction to Fasay’il village, where a continuous white line indicates that this entrance to the village is ‘not recognised.’

Moreover, the Palestinian Bedouin community of Fasay’il Al Wusta about 1km northwest of the Tomer Better Place Station has found itself living in the ‘worst place’: they are prevented from accessing running water or electricity, they are prevented from tarmacking the stony track that is the only road access to their homes; and they have been subjected to the violent destruction of their homes four times since October 2011.

Better Place profits from the occupation, works to sustain the apartheid regime and thus deserves no less than boycott, exposure and closure.

Better Place company profile

Formally established in California in 2007, the company has since expanded to Europe, the Middle East, North America and East Asia. In 2008, the company was set up in Israel in a partnership with the French-Japanese car conglomerate Renault-Nissan, backed by Israeli President Shimon Peres and former Prime Minister Ehud Olmert.2 Then, the company announced that electric vehicles would become available to consumers in 2011, claiming that its innovative business model would transform the transportation market. However, by October 2012, the company has only sold 500 cars in Israel and 200 in its second biggest market, Denmark.3

Formally established in California in 2007, the company has since expanded to Europe, the Middle East, North America and East Asia. In 2008, the company was set up in Israel in a partnership with the French-Japanese car conglomerate Renault-Nissan, backed by Israeli President Shimon Peres and former Prime Minister Ehud Olmert.2 Then, the company announced that electric vehicles would become available to consumers in 2011, claiming that its innovative business model would transform the transportation market. However, by October 2012, the company has only sold 500 cars in Israel and 200 in its second biggest market, Denmark.3

According to Who Profits, the company is run by the Ofer family, which holds some 30% of the company’s shares through its holding company Israel Corporation.4 Founding investors also comprised Morgan Stanley, Vantage Point Venture Partners, and a group of individual private investors managed by Michael Granoff, including James Wolfensohn, Edgar Bronfman, Sr. and Musea Ventures.5

In February 2012, the company opened its first electric vehicle demonstration center in the Pi Glilot compound in the Ramat Hasharon district in Tel Aviv. At the same time, in partnership with Dor Alon, one of Israel’s leading petroleum supplier and Israeli representative of Chevron and Aral lubricants,6 Better Place is making battery switch stations available at an increasing number of Dor Alon’s facilities,7 including next to Tomer and Qalya settlements in the Jordan Valley.

(1) http://israel.betterplace.com/Our_Vision/begining/Pages/default.aspx [last accessed 23/10/12]

(2) http://www.betterplace.com/press-room/Renault-Nissan-and-Project-Better-Place-Prepare-for-First-Mass-Produced-Electric-Vehicles [last accessed 23/10/12]

(3) http://www.haaretz.com/news/features/david-s-harp/shai-agassi-is-us-israelis-distrust-of-the-big.premium-1.469017 [last accessed 23/10/12]

(4) http://www.whoprofits.org/company/better-place [last accessed 23/10/12]

(5) http://www.betterplace.com/press-room/Shai-Agassi-Launches-Alternative-Transportation-Venture [last accessed 23/10/12]

(6) http://www.whoprofits.org/company/dor-alon [last accessed 23/10/12]

(7) http://www.betterplace.com/global/progress/Israel [last accessed 23/10/12]