Not a drop: Israel takes a spring and childhood memories with it

Monday, 19 December 2011 09:26 Emma Mancini for the Alternative Information Center (AIC)

Mustafa Tamimi was killed during the weekly protest in Nabi Saleh, which demonstrates against the occupation, illegal Jewish settlements, and Israel’s appropriation of the village spring. While Nabi Saleh might be one of the most visible struggles around water, there are numerous other places in the West Bank where Israel has taken water resources and diverted them for settlements. A Palestinian man discusses his childhood connection with one such spring…

Abdallah stares at the empty channel, his face resigned. On this beautiful sunny day, he hadn’t expected to find the creek of his childhood completely dried up. Beside the waterless channel, there is a huge Israeli pump, protected by electric fences.

“Al Auja was a water spring, where the creek started”, Abdallah Awudallah, a 29-year-old from the Bethlehem district’s Ubbedyia village, tells the Alternative Information Center. He came here with a group of internationals to discuss Israeli confiscation of land and water in the Jordan Valley. The tour would have finished in Al Auja water spring. But the water was gone.

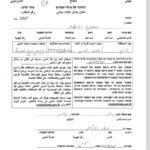

Not a drop: the Israeli authorities have built a generator in order to draw up water from the once-flowing creek and to send it to the agricultural settlements in the Jordan Valley. The spring, which used to serve Jericho, is now reserved exclusively for Israeli settlements.

“In Arabic ‘auja’ means ‘in the opposite direction’” Awudallah explains. “We used to call the creek like that because for long stretches the water ran up and not down. Because of the high pressure and speed, the water received the boost it needed to flow [upstream].”

Not only was the spring unique, it colored the desert green. It also served as an educational tool for Palestinian children, Awudallah adds.

“Many schools in the West Bank used to bring the students for a trip to Jericho and Al Auja: it was the perfect place to spend a day between water and fish and to study one of the basic vital resources. No Palestinian schools can organize a journey in Tiberias, in Palestine ’48, because they lack the necessary permits to enter Israel. So, Al Auja was the only place to feel the importance of water.”

“The first time I came here,” he goes on, “I was 15 years old. It was in 1997. The first time I saw a creek and fish playing around our feet, immersed in the water. Alongside the creek, the grass was green. Many Palestinian families used to come to Al Auja for a picnic. But always warily, in fear: the spring is located in Area C, under Israeli control, and many Israeli organizations organized tours here. The Israeli army often pushed the Palestinians out: I remember arrests, searches.”

“And today, I find it empty,” Awudallah says, his eyes fixed on the channel. “This place is a desert, there´s no life whatsoever. I feel empty, as sad as this channel. I wonder how the Bedouin community of Ras Al Auja is living now: they settled here because of the water. They had fresh grass for sheep and goats and drinking water. Now, for sure, they are forced to buy tanks from Israeli companies: every tank costs 200 shekel.”

Activists from Jordan Valley Solidarity (JVS)–a network of local popular committees and international supporters–explain that Al Auja was an oasis once. Families used to come to the spring to fish, swim, and picnic amidst the banana groves. In 1972, the Israeli private company Mekarot–51% of which is owned by the State of Israel–started digging two deep water wells in Al Auja, decreasing the capacity of the aquifer.

Some years ago, the Israeli authorities completed the project by constructing a pump that draws water directly from the spring, drying up the creek completely. Water was appropriated from the Palestinians of the Jordan Valley in other ways–while Israelis are allowed to dig wells up to a depth of 300 meters, Palestinians can’t exceed 160 meters. Thus, the water resources, become, in practice, inaccessible.

In the Jordan Valley, the Palestinian communities are forced to buy tanks from Mekarot company, that monopolizes the water resources in the West Bank. According to JVS, Palestinians pay 200 shekels (over 50 US dollars) per water tank plus transportation costs.

“Each cubic meter of water costs the Palestinian communities 30 shekels,” Fathy Khidrat, member of the Jordan Valley Solidarity, says to the AIC, “while [Israeli] settlers pay three shekels per cubic meter.”

While Palestinians constitute a majority in the West Bank, settlers consume four times as much water, on average per capita.

The nearby village of Ras Al Auja, with a population just over 4000, faces additional problems. After the 1967 war, the Israeli authorities created a security zone alongside the Jordan Valley, an operation that resulted in the confiscation of more than 30,000 dunam belonging to Ras Al Auja.

According to JVS, the construction of road 90 has made things worse. Reserved for settlers, 90 cuts through the West Bank from north to south. The road bypasses Jericho and cuts through Ras Al Auja village, while its residents aren’t allowed to use it.

Last spring, the Vittorio Arrigoni school (re-named in honor of the Italian activist killed in Gaza last 15th of April) was destroyed by Israeli military bulldozers. The school was built by JVS and served more than 130 children from the community.

In addition, there are several settlements surrounding the village and a military checkpoint controls the southern area of Ras Al Auja. The unemployment rate is high, according to JVS, “Al Auja survives because the men work illegally inside the settlements. The area feels like little more than a work camp, reminiscent of the township of apartheid in South Africa, with all the men away during the day, at work in the settlements.”