Maan: Parallel realities: Israeli settlements and Palestinian Communities in the Jordan Valley 2012

Maan Development have produced a new publication about “how the various subsidies provided to settlements reinforce the numerous Israeli limitations placed on Palestinians living in the same area, creating a segregated, dichotomous population based on overt discrimination”.

Maan Development have produced a new publication about “how the various subsidies provided to settlements reinforce the numerous Israeli limitations placed on Palestinians living in the same area, creating a segregated, dichotomous population based on overt discrimination”.

Parallel realities: Israeli settlements and Palestinian Communities in the Jordan Valley 2012

Introduction

The Palestinian Jordan Valley is the eastern section of the West Bank, running adjacent to the Jordan River. Starting at the Dead Sea and extending approximately 70 km north to the border with Israel, the Jordan Valley is approximately 15-20 kilometers wide and, at 1,700 square kilometers, covers around 28.5% of the West Bank. The rich agricultural land, temperate climate, and abundant water resources offer enormous agricultural, economic and political potential for the Palestinian people.

However, this potential has been denied to the Palestinian citizens of the Jordan Valley by the policies of the Israeli military occupation and the continuing illegal expansion of Israel’s civilian settlements. In fact, the first civilian settlements in the West Bank were built in the Jordan Valley. Throughout the years of occupation, the Israeli government began actively promoting the settlement enterprise by offering a number of far-reaching economic and social benefits to those Israelis that emigrated to the illegal settlements.

Consequently, Jordan Valley settlements have grown at a steady rate, aided by governmental aid that expanded important settlement infrastructure and enriched many individual settlers. In 1993, the implementation of the Oslo Accords allowed Israel to strengthen its means of oppression in the region; the Oslo Accords designated 95% of the Jordan Valley as Area C, temporarily legitimizing full Israeli military and civil control for the inhabitants of the region.(1)

Although there are currently 56,000 Palestinians and only 9,400 Israeli settlers in the Jordan Valley, the living standards of the latter group are vastly superior. While the Israeli settlers benefit from generous aid from the Israeli government, Palestinians are nearly completely prevented from any sort of development in 95% of the Jordan Valley. Consequently, neighboring Palestinian and Israeli settler communities provide a stark and telling juxtaposition that demonstrates the racial discrimination that guides Israeli policy in the Jordan Valley. By directly subsidizing settlements’ growth, expansion, and development while completely prohibiting even the most basic of services to Palestinians, Israel has ensured that the Palestinians cannot overcome the discriminatory gap in the quality of life between the two populations.

This publication will examine how the various subsidies provided to settlements reinforce the numerous Israeli limitations placed on Palestinians living in the same area, creating a segregated, dichotomous population based on overt discrimination. MA’AN Development Center interviewed six Israeli settlers, including members of the Jordan Valley Regional Council as well as members of local municipalities, and 30 Palestinians, including members of village councils. Interviews were conducted from August 2011 to February 2012. This study is based on a number of specific case studies that are meant to highlight the inherent difference in Israeli policy towards the Palestinians and Israeli settlers in the Jordan Valley.

The Foundations for Discrimination: the origins of the settlement endeavor

While the Israeli military immediately occupied the West Bank and Gaza after the 1967 war, Israeli control expanded not long thereafter to include a ‘civilian occupation,’ in the form of Israeli civilian settlements. (2) While an official master plan

for the creation of settlements has never existed, many prominent Jewish figures have developed proposals for Jewish settlement in the occupied West Bank and Gaza Strip. Most of the plans focused on specific areas of the occupied territory, never as a whole entity. (3)

The most widely publicized plan, developed by Yigal Allon in July 1967, advocated creating a buffer zone in the Jordan Valley against the neighboring Arab countries, to be used by the military and Israeli settlements in preparation for future annexation to Israel. According to the Allon plan, the densely-populated Palestinian areas would either be given to Jordan for administrative control or possibly granted local autonomy. The purpose of the Allon plan was to incorporate as much land, and as few Palestinians, as possible in order to avoid the responsibility for Palestinians while easing annexation of the area. (4) Allon explained the Jordan Valley buffer zone by saying “the settlements…guarantee our security, leaving a void that can develop according to our wishes without harming our security.” (5)

Initially, the Israeli government formed settlements by demilitarizing existing Nahal military outposts and handing over control to Israeli civilians.(6) Within only a few years, an overwhelming majority of the Nahal outposts in the West Bank, and especially the Jordan Valley, were converted to civilian control. (7) Although the Israeli government never formally adopted the Allon plan, “the government in fact went by in its settlement policies in the occupied territories.”(8) These civilian settlements had “very far reaching political implications and were designed to establish a new reality that would influence the future political situation.” (9)

The political consequences of the Israeli settlement project are two-fold. Firstly, the strategically placed settlements allow Israel to dictate any future borders of the state by utilizing an argument of demographic necessities. (10) Secondly, the proliferation of settlements and outposts across Palestinian land provides Israel with ‘bargaining chips’ during negotiations with its Arab neighbors and the Palestinian Authority. (11) In addition to their political implications, the economic potential of the settlements in the Jordan Valley was paramount in the decision to establish and expand the settlement project in the region. These settlements are able to secure valuable ground water in the Jordan Valley for Israeli use, develop export crops and industry, restore ancient sites, and develop the tourism sector surrounding the Dead Sea. (12)

Since 1967, the settlements of the Jordan Valley have grown at a steady rate and, currently, 36 settlements house approximately 9,400 Israeli settlers.(13) These settlers enjoy a high standard of living that is maintained by subsidies from the Israeli government, in addition to other quasi-governmental and private organizations. Despite being against international law, the funding of settlements in the occupied Palestinian territories by Israel and various independent organizations has been, and continues to be, a major reason for the success of these illegal communities.

Agriculture as a means of development

Immediately after the 1967 war, somewhere between 70,000 and 300,000 Palestinians were driven from the Jordan Valley to other areas of the West Bank or Jordan.(14) The removal of thousands of Palestinians in conjunction with the area’s economic and agricultural potential made the Jordan Valley ripe for Israeli settlement. Immediately after the war, the Israeli government began investing heavily in Jordan Valley settlements in order to quickly relocate Israeli civilians to the region as well as to prepare the new settlements to efficiently maximize and utilize the resources available. (15)

In the first phase of settler expansion, some of the military outposts transformed into civilian cooperative, agricultural moshavim and kibbutzim based on models already existing within Israel proper. (16) Meanwhile, settlements in the southern Jordan Valley developed tourist-based initiatives due to their proximity to the Dead Sea and religious sites.(17) Agriculture, however, has been the main vehicle for economic success in the Jordan Valley settlements. The prosperity of the settlements’ agricultural ventures is a direct result of massive government investment in agricultural technology. The involvement of the Israeli government in the development of important agricultural infrastructure in the Jordan Valley has given the settlements the ability to diversify their agricultural production. Governmentally-subsidized water irrigation systems, for example, has allowed the settlements to increase production at a cheaper rate than the Palestinian villages.(18) Ultimately, the idea that drove the settlement enterprise in the Jordan Valley was that:

“With the aid of large scale capital investment in the development of water resources and the use of agrotechnical know-how that [had] not been available to the Arab farmers, it [was] possible to raise large crops of winter vegetables and fruits which could be sold at high prices in the European markets. The settlement [Allon] plan also ensured the geographical continuity of the settlements, which greatly facilitated the supply of services.”(19)

After 1979, Israel began declaring land already in use by settlements, or land expected to be added to settlements, as ‘state land.’ Under this policy, most of the ‘state land’ was under the jurisdiction of the Custodian of Abandoned Property.(20) The Zionist movement first employed this strategy before the creation of the State of Israel, to settle Jewish populations in the British Mandate Palestine in noncontiguous communities for maximum land domination.(21)

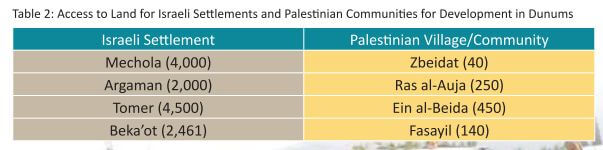

The use of this strategy in the Jordan Valley has resulted in Israeli control over a disproportional amount of the West Bank. In terms of urban areas, the settlements in the Jordan Valley are even sparser than other Israeli settlements. The built-up areas currently total 6,661 dunums, or less than half a percent of the Jordan Valley. Their municipal area, or the area over which they have complete control is 28 times greater than their urbanized area. When all the different settlement regional councils that have land in the Jordan Valley are included, then a total of over 90% of the Valley is under direct settlement control.(22)

The matrix of subsidy distribution to israeli settlers

Since shortly after the occupation in 1967 and continuing until present day, every Israeli administration has:

Implemented a vigorous and systematic policy to encourage Israeli citizens to move from Israel to the West Bank…One of the main tools used to fulfill this policy is the provision of significant financial benefits and incentives…Two types of benefits and

incentives are granted by the government: support granted directly to the citizens by defining settlements as ‘national priority areas,’ and support granted to local settlements in the West Bank in a manner that favors them in comparison to settlements inside Israel.(23)

Communities that the Israeli government defines as ‘National Priority Areas’ are entitled to certain benefits under Israeli law. Although the West Bank is illegally occupied territory under international law, Israel defines the entire West Bank as a National Priority Area. The government gives Israeli civilians subsidized housing and education, in addition to industrial, agricultural, and touristic benefits as incentives to live in these areas. The National Priority Area designation is meant “to encourage positive migration to the communities and to assist in finding solutions to ease the housing situation…”(24) In addition, various monetary and infrastructural benefits are given to local Israeli authorities to be used for economic projects such as creating or renovating tourist sites, individual farms, and other projects.(25)

These policies have enticed many Israelis from lower socio-economic backgrounds to move to settlements in order to enjoy a higher standard of living. In fact, the average household income in settlements is 10% higher than in Israel proper, and unemployment in settlements is typically half the rate of unemployment within Israel.(26) As of February 2012, 70 of the 121 Israeli settlements in the West Bank were designated as National Priority Areas,(27) including all the settlements in the Jordan Valley.(28) In addition to official aid from the government, every National Priority Area settlement in the occupied Palestinian territories has received additional budgetary grants and benefits on the initiative of individual ministers in the Knesset.(29)

In 2006, the legality of the National Priority Areas was brought before the Israeli Supreme Court, which found the designation to be discriminatory against non-Jewish communities and overly beneficial to Israeli settlers. Although the designation requirements were slightly altered in 2009, the law still greatly favored the settlements.(30) The government was supposed to terminate the policy by 13 January 2012, but instead it extended the practice for a third time.(31)

The governmental support given to settlements, either through the National Priority area legislation or through the initiatives of individual ministers, is extensive and unbalanced. For example, between 2000 and 2002 settlers constituted only 43% of Israelis living in National Priority Areas, but received 63% of governmentally allocated funds. In addition, assistance for infrastructure, public institutions, and planning amounted to 36,024 NIS per apartment in settlements, but only 10,166 per apartment in Israel proper.(32)

Local municipalities are often used as an intermediary between the Israeli national government and the final beneficiaries of governmental aid.(33) The municipality, having a form of legitimacy as a small governmental body, is able to actively lobby on behalf of the settlers for almost anything agreed upon through a majority vote. In addition to the substantial benefits that settlers receive from the municipality, the settlements are also accustomed to benefits such as more ambulances, new clinics, paramedics, etc. In the words of a member of the Jordan Valley Regional Council, “we are in charge, or we make sure we get the services we are entitled to.”(34)

The governing committees within settlements and regional councils, consisting or representatives of several settlements, are also indispensible for the procurement of special settlement benefits.(35) The governing committee’s role in settlements is to distribute the services that are provided by the regional council or the state government. When a settler wishes to claim a service, he or she must contact the committee director or manager, who lobbies the regional council or national government for the benefits. The governing committee therefore acts as a distribution center for the benefits, creating a larger matrix through which it becomes difficult to track the exact flow of money.(36) The regional council’s job is to “develop the services” and “provide services to act as the government” in the Jordan Valley.(37)

Settlements also receive significant financial support from Zionist organizations across the world. Many American Zionist organizations, such as The One Israel Fund, The Jordan Valley Development Fund, and the Shiloh Israel Children’s Fund, directly aid the expansion of Israeli settlements. From 2005 to 2007, the American Friends of New Communities in Israel donated nearly $500,000 to settlements in the West Bank. Likewise, the Christian Friends of Israeli Communities donated $2.27 million to settlements between 2006 and 2008. Moreover, in the last ten years, American Zionist organizations have helped resettle former Gaza settlers in the West Bank, built several psychological rehabilitation centers, funded settlement police forces, constructed several libraries and a recreational center, funded at least three educational programs, constructed a number of water reservoirs for settler use, and built nine kindergarten play areas in the Jordan Valley.(38)

Israeli civilians are actively encouraged by the State of Israel, individual governmental officials, and international Jewish organizations to move to the occupied Palestinian territories through the provision economic benefits that are unavailable to those living within Israel’s recognized borders. These benefits allow the settlers to live a more comfortable lifestyle than most Israelis, and much superior to that of the average Palestinian, especially ones living in the Jordan Valley.

Specific benefits to settlements

Settlers enjoy subsidies predominantly in housing, education, agriculture, industry, and tax policy. From the Israeli government, the benefits and incentives are distributed through six main ministries: Housing and Construction; National Infrastructure; Education; Trade and Industry; Labor and Social Affairs; and Finance.(39) Individual political parties also are able to contribute or allocate state funds to settlements. In 2004, for example, the National Religious Party alone contributed $23 million to settlements.(40) Additionally, the Israeli government alters settlement benefits to target specific areas. For example, when the Israeli government was trying to persuade families to move to the Jordan Valley in the early 2000s, the first 200 families who applied for a house construction permit were granted $22,800, free university tuition for one spouse, and another grant of $2,700 if the couple found employment in their new settlement.(41)

The Ministry of Construction and Housing provides financial assistance for those who purchase a new apartment or build a home in settlements located in National Priority Areas. Under the current legislation, the Ministry will provide a grant to settlers, covering up to 50% of the expenses of building a home or buying an apartment.(42) Although the Israeli government used to subsidize nearly 100% of housing costs in the Jordan Valley, according to a member of the Jordan Valley Regional Council, “it is still cheaper to build a house [in the Jordan Valley], cheaper than anywhere else.”(43) While official governmental housing subsidies in the Jordan Valley have fallen, every settler that relocates to the area receives further housing benefits through unofficial sources; every settler in the Jordan Valley, for example, receives a free plot of land from the settlement division of the World Zionist Organization (WZO).(44) The WZO is a quasigovernmental organization; while technically independent from the Israeli government, it is completely funded by it.(45) The close links between the WZO and the Israeli government were highlighted in 2009 when a document was presented to the Israeli Supreme Court that revealed the WZO, acting as an agent of the Israeli government, had confiscated private Palestinian land and had given it to Israeli settlers.(46) Outside of land grants, the WZO also allocates large sums of money into various other projects. Shir Hever, an Israeli economist, estimates that from 2000 to 2002, the WZO invested over $100 million to agricultural projects in settlements.(47)

Furthermore, sizeable government subsidies to the Israeli agricultural industry in the Jordan Valley have helped maintain the high profitability of this sector. Under the National Priority Areas laws, Jordan Valley settlers are entitled to generous financial benefits, including: grants covering up to 25% of the cost of establishing agricultural enterprises; a subsidy for agricultural tourist projects; and tax reductions on profits ranging from 25-30% on investments.(48) Israeli companies are also exempted from paying the Value Added Tax for exports of fresh fruits and vegetables to the European Union.(49) Additionally, the Israeli government aids the settlements in subverting the European Union boycott against settlement goods. This is extremely important for Israeli settlements in the Jordan Valley as approximately 60% of settlers work in the agricultural sector.(50) Moreover, as B’tselem notes, “in communities classified as agricultural,” the Land Administration also offers “some 150 dunums of land for employment, which is double the amount allocated for this purpose in areas not classified as National Priority Areas.”(51)

Individuals, organizations, or corporations are also offered monetary incentives for investing in settlements. The Israeli Ministry of Industry, Trade and Labor offers investors a grant of 15-20% of any investment in the tourism industry, up to 140 million shekels (approx. $37 million). Investors are also granted a 25% reduction in corporate tax payments or, alternatively, a ten-year full tax exemption on all undistributed income.(52) The Israeli government offers specific employment benefits to companies located in settlements. Eligible companies and organizations receive up to “135,000 NIS ($35,000) over a period of 30 months or 4,500 NIS ($1200) per month.”(53)

Settlements also benefit from highly preferential tax laws. As B’tselem notes, “local taxes in the settlements are lower than in Israel, even though most settlers have a relatively high income.”(54)

Between 2000 and 2006, according to the Adva Center, settlements in the West Bank paid 60% less tax per capita than Israeli citizens living in Israel proper.(55) Foreign companies working within settlements also benefit from the tax system. The Ministry of Industry, Trade, and Labor offers a 50% reduction on research and development centers established by foreign companies in National Priority Areas. In addition to massive tax breaks, foreign companies that establish a research and development center in settlements are eligible for a further 20% “investment grant on specific projects.”(56)

Case Study: Comparison Between Preschools in the Palestinian Village Zbeidat, and the Israeli Settlement Shadmot Mehola

Palestinians living in the village of Zbeidat live in extremely limited circumstances, as Israeli authorities only allow the 2,000 residents to build on approximately 42 dunums of land, approximately the size of two football fields. If the residents build outside of this area, they risk the Israeli military issuing the structure a demolition order. Therefore, when it became necessary to construct a new preschool four years ago to accommodate the increasing number of children, Zbeidat citizens turned to a dilapidated building, a last resort in a situation with no alternative.

From the beginning, two women have run the preschool, which they decided to open due to the abundance of young children playing in the dangerous streets. When Huda and Subhiya decided to open the preschool, they requested funding from the Palestinian National Authority (PNA). But on account of budgetary constraints, the PNA was, and continues to be, unable to provide any financial assistance to the preschool. Consequently, the school must accommodate for 40 kids solely on the funds the women themselves can raise. Most children attend for nine to ten months, but the parents are expected to pay 50 NIS a month per child, an amount which many families can’t afford. The 50 NIS fee is required to cover the bare minimum in operating costs and supplies for the preschool. Unfortunately, the preschool suffers from inadequate funding and cannot provide an environment conducive to learning. Most of the tables and chairs need replacement, in addition to the classrooms lacking essential teaching materials such as pens, pencils, paper, and English-Arabic language instruction materials. Furthermore, one bathroom must currently accommodate for the 40 children and instructors.(i)

Meanwhile, in the Israeli settlement of Shadmot Mechola, the over 550 settlers have access to two preschools. The preschools start for children at the age of three and are completely funded by the State of Israel. The preschools are in appropriate structures built for their intended use as a school. The government fully supplies the classrooms with new desks, chairs, games, and even provided a modern kitchen with a refrigerator. The smaller preschool has one teacher and 12 children, while the larger school has 20 children split between two teachers. The smaller preschool has six rooms, including a main area, a kitchen, two secondary rooms, a room for coats and backpacks, a separate bathroom for boys and girls, all of which are consistently cleaned and maintained by a custodian. There is an outdoor play area equipped with sun protection and numerous toys for the kids to use. The building as a whole is modern, well maintained, and constantly staffed with well-paid government employees.(ii)

i- MA’AN Development Center Interview and Field Visit 24 December 2011

ii- MA’AN Development Center Interview and Field Visit 11 December 2011

Education

In the education sector, Israeli settlements receive more assistance from the Israeli government than Palestinians in Area C or Israelis living in Israel proper. The salaries of government teachers living in settlements are 12-20% higher than Israeli teachers inside Israel’s recognized borders. The government also covers 80% of rental costs, 75% of salary-related expenditures, and all travel expenses. Moreover, the government covers the teachers’ contribution to the continuing education fund (hishtalmut) and partially funds the tuition of settlement teachers for academic studies. Such generous governmental benefits have encouraged a higher proportion of settlers to join the education sector: 25.1% of the population in settlements works in education compared to 12.9% in Israel proper.(57)

Schools in the settlements also are improved by additional governmental funding. School days are extended by 20%, computer systems are completely government-funded, and the government covers 90-100% of all transportation costs for students. Overall, the budgeted amount for public institutions in the settlements, including day care centers, libraries, and community centers, is 54% higher than in Israel proper.(58) Informal educational institutions in settlements also receive generous funding from the Israeli government; community centers, which play a central role in Education the lives of many Jordan Valley settlers,(59) each receive a 100,000 NIS development grant from the government.(60)

Unsurprisingly, the students in settlement schools greatly benefit from the expanded governmental funding. The government pays for all matriculation exam fees and priority is given to settlement students in the state university application process. Additionally, settler students in the Jordan Valley are provided a 30% discount on university tuition if they matriculate at Ariel University, which is located outside of the Palestinian city of Nablus in the Ariel Settlement.(61)

In the Jordan Valley, the governmental funds allocated for the transportation of students are particularly important. The Jordan Valley Regional Council, for example, manages two schools for settlers: one for grades 1-6 at the Jordan Valley Regional Council in the center of the Jordan Valley near the settlement of Massu’a, and one for grades 7-12 in the settlement of Ma’ale Ephrayim. This specific regional council, though, represents over 4,000 settlers dispersed throughout 21 settlements along 60km of Road 90, the main highway in the Valley. The size of the Jordan Valley and the distances between the settlements make transportation extremely important for students. Unsurprisingly, transportation to and from school is provided for all settler students free of charge throughout the entire region.(62)

Water

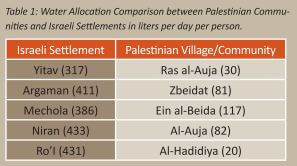

Israeli settlements in the Jordan Valley enjoy a nearly endless supply of water at a subsidized rate. The quasi-governmental water company Mekerot began digging wells exclusively for settlers after 1967. With substantial government investment, the water carrier has connected every Israeli settlement in the Jordan Valley to the Israeli water network. Meanwhile, governmental subsidies greatly lower the cost of water for settlers. The average settler family pays only 105 NIS per month, which constitutes .9% of a family’s monthly income.(63) For single adults, the number can be as low as 30 NIS.(64) In addition, the government gives reclaimed wastewater from East Jerusalem to settlements in the Jordan Valley for agricultural usage.(65) As a result of the governmental water subsidies, the average Israeli settler in the Jordan Valley uses 487 liters a day for just household use; in the northern Dead Sea area settlers use 727 liters a day, three times the usage of citizens in Israel proper.(66) When factoring in agricultural usage, this figure drastically increases to around 1,312 liters per settler, which is almost 18 times greater than the average per capita usage of water available to West Bank Palestinians.(67) Furthermore, governmental aid with regards to water has allowed nearly every settlement in the Jordan Valley to include large swimming pools for public usage by the settlers.(68)

Further Subsidized Community Services

The Israeli government provides settlements with most essential services and goods if not freely, then at a greatly discounted rate. The government, for example, funds all trash collection, health care and the police services, while electricity, water and internet are provided at extremely reduced rates. In fact, the Israeli government participated in the construction of the electricity and internet networks, utilities which quasi-independent companies now control. According to a member of the Jordan Valley Regional Council, the settlements “have government support for most of the infrastructure that was built in the region, in almost all of the public buildings.”(69) Most settlements also have their own clinic, while a new, centralized regional clinic is being developed near the settlements of Tomer and Petza’el.(70)

Likewise, the Israeli government is actively promoting tourism in the West Bank by providing incentives to develop the industry, particularly around the Dead Sea. The Israel Land Administration, for example, reduces the leasing fees by 69% on land intended for industrial use or tourism in settlements. As a result of the governmental aid, many settlements are attracting higher numbers of tourists from all over the world, with many staying in guest houses located within the settlements.(71)

Case Study: Ras al-Auja and Yitav: The Fight Over Water

The Bedouin community in Ras al-Auja is originally from a village in the northern Naqab desert, within the borders of modern-day Israel. In 1948, Israeli authorities forcibly removed the community and sent them to the West Bank where they settled

south of Hebron in the area of Susiya.(i) A few years after the 1967 occupation of the West Bank, the community again relocated to the area northwest of Jericho. When they arrived, the local springs supplied plenty of water and the abundant presence of grass meant the land was beneficial for animal grazing.

The Israeli restrictions that intensified with the implementation of the Oslo Accords greatly hindered the ability of Palestinians to maintain their traditional livelihoods. Since Ras al-Auja is located in Area C, the PNA cannot provide the community with any social services. At the same time, Israel does not recognize the community as legitimate. Thus, to maintain their lifestyle, the Bedouin must buy water tanks from the Israeli water company Mekerot at exorbitant prices. This places a huge burden on the Bedouin, as the price of one water tank can reach 10-15 times as much the price of piped water. Residents of Ras al-Auja, in order to sustain their livestock herds, must bring in 25-30 tanks of water per day. Each tank is three cubic meters and costs approximately 60 shekels, or 20 shekels per cubic meter.(ii) The Bedouin prioritize their livelihood, generally splitting their water usage in favor of their animals (60%) as opposed to personal use (40%).

The settlement of Yitav began absorbing many former Soviet Union Jews in the 1990s, which led to the settlement’s expansion at a rapid rate, monopolizing the surrounding water resources. During the second Intifada, Israel constructed multiple wells exclusively for the settlements of Yitav, Vered Yericho, Niran, Na’ama, and Rimmonim. The deep Israeli wells that provide endless water for the settlers have dried up the few natural water resources available to Palestinians. In Ras al-Auja, the essential network of canals and natural springs are completely dry eight to nine months of the year.(iii)

The settlers, in comparison to the Bedouin herders, rely little on water for their living, as Yitav does not support a large agricultural industry. Even without major agricultural enterprises the settlers enjoy unlimited personal water usage and face no shortages throughout the year. At the same time, settlers only pay around 1.79 shekels/cubic meter, or nearly eight times less than what the Bedouin pay.(iv)

As the situation stands today, the Israelis monopolize all the natural water sources and continue to deny the Palestinians access to large wells built for the exclusive use of the settlers.

By the Numbers

- 1,000 Palestinians (and their livestock) live on 250 dunums of land, leaving 0.25 dunums per person.(v)

- Between 117-130 Israeli settlers have access to over 1,000 dunums of land, allowing 7.7 dunums per settler.(vi)

- The average Palestinian in Ras al-Auja uses only 30 liters of water per day for personal use.(vii)

- The average Israeli settler in Yitav is allocated 317 liters of water per day.(viii)

- Israelis in Yitav consume 10.5 times more water than Palestinians while Palestinians pay 11.17 times more for each cubic meter.

Restrictions on Palestinians in the Jordan Valley

While Israeli Jews are actively persuaded by the Israeli government to move to the occupied Palestinian territories, simultaneously the Palestinians living in the Jordan Valley are pressured to abandon their homes and traditional lifestyles. Israeli authorities, through their extensive restrictions on Palestinian development, have greatly inhibited the ability of Palestinians to lead a normal life. By confiscating and reallocating resources, such as land and water, while also greatly limiting freedom of movement and construction, Israel has effectively eliminated the ability of Palestinians to develop in the Jordan Valley. As a consequence to their stifled expansion and modernization, many Palestinian communities have been forced to leave the area.

Water

The Israeli settlers in the Jordan Valley have no shortages of services as the settlements are all connected to modern water, electrical and communication networks. Israeli settlements receive ample supplies of water from the Israeli national water carrier. Comparatively, only 37% of Palestinians in the Jordan Valley stated that water was ‘available’ to them while only 2% of respondents said sanitation services were available.72 Meanwhile, every Israeli settler in the Jordan Valley is connected to water and sanitation networks.(73)

Water is perhaps the most vital resource in the Jordan Valley. While there is ample water in underground aquifers, natural streams, and the Jordan River, Israel holds complete control over the allocation of water, a practice which has become undeniably discriminatory. For the Palestinian community in the Jordan Valley, adequate access to water is paramount to survival; 42% of Palestinians in the Jordan Valley, north of Jericho, depend on agriculture or animal husbandry as their main source of income. Without water, both of these professions would disappear.(74)

Prior to 1967, the Jordan River was a prominent source of water for the whole of the Jordan Valley. Immediately after the occupation in 1967, Israel took complete control of all water sources in Palestine and, importantly, completely denied Palestinians access to the Jordan River. Since that time, Israel has continued to deny Palestinians the right to water by demolishing Palestinian wells, cisterns, and other water sources. Israel has destroyed 140 water pumps and has confiscated 162 Jordanian-era water projects.(75)

From January 2009 to August 2011, the government demolished 44 cisterns and rainwater collection structures in Area C, the vast majority of which were in the Jordan Valley. The demolitions affected 13,602 Palestinians and displaced 127 people, including 104 children.(76)

In 1967, there were 774 operational wells; by 2005, Israel had reduced this number to 328.(77)

While Israeli settlers are provided with large quantities of water for agricultural development as well as personal use, the restrictions on the Palestinian water usage are so extreme that many Palestinians have been unable to make a livelihood in the Jordan Valley and forced to relocate.(78)

Beyond Israeli limitations on access to surface water sources, the Palestinians are denied the ability to construct new water structures. Israeli settlers in the Jordan Valley, on the other hand, face no such bureaucratic or military obstacles. When a new well or water structure needs to be built for the settlers, the local or regional government applies for a permit from the Israeli government. Interviews with settlers reveal that the government quickly provides these permits and rarely rejects applications from settlements.(79)

After a permit is secured, Mekerot builds the water structure for the settlement. When Palestinians wish to build a well, on the other hand, they follow a different process; they must apply to the Joint Water Committee (JWC), a committee consisting of Israelis and Palestinians meant to oversee and authorize water projects in the West Bank. Although the purpose of JWC is to regulate all water issues in the West Bank, it has no authority over the Israeli settlements. Effectively, this Committee provides Israel with a veto over Palestinian water decisions while Palestinians have no influence over water issues in settlements.(80)

Consequently, the JWC prevents many Palestinian water projects. In fact, the World Bank notes that “106 water projects and 12 large scale wastewater projects are awaiting JWC approval, some since 1999.”(81)

Palestinians also must apply to the Israeli Civil Administration, which must approve all Palestinian water projects in Area C. The additional bureaucratic obstacles to Palestinian water development have resulted in far fewer Palestinian water projects. Only one Israeli project has been denied since 1993, while only half of all Palestinian projects (by dollar value) have been approved.(82)

Due to these restrictions, approximately 67% Palestinians in the Jordan Valley do not have water available to them and are forced to purchase Mekerot water tanks that are extremely expensive.(83)

The normal price for Palestinians for water from a water network is 2.6 NIS per cubic meter; in contrast, the price of water tanks ranges from 14 to 37.5 NIS per cubic meter. Moreover, the price of tanked water has increased by 101%-153% since the beginning of the Second Intifada, caused mainly by increased restrictions on movement, resulting in some households spending upwards of 40% of their income on water alone.(84)

As a result, Palestinians pay a higher individual cost and a much greater percentage of their family income to water in comparison with Israeli settlers.(85)

Throughout the Jordan Valley, Israeli settlers have access to and utilize much more water than Palestinians. As mentioned above, Israeli settlers in the northern Jordan Valley were allocated 487 liters per settler per day in 2008 and settlers in the Northern Dead Sea area were given 727 liters per day.(86)

Comparatively, Palestinians in the Jordan Valley barely have access to any water. In the northern Jordan Valley, the village of al-Hadidiya consumes 20 liters per day per person, which approaches the World Health Organization’s absolute minimum and puts the community in danger of water-borne epidemics.(87)

Next to al-Hadidiya are the settlements of Roi and Beqa’ot, which consume 431 and 406 liters per person per day, respectively. Al-A’uja, a Palestinian village just north of Jericho with 6,000 inhabitants, uses just 82 liters per person a day, while the agricultural settlement of Niran uses 433 liters. Likewise, Zubeidat, a congested Palestinian community of 2,000, currently uses 81 liters of water a day while the neighboring settlement of Argaman consumes 411 liters.(88)

Education

As nearly 95% of the Jordan Valley is designated as Area C, and thus under Israeli military control, the Palestinian National Authority (PNA) is unable to provide any sort of substantial educational assistance to these areas. The few areas where the PNA has autonomy are scattered and do not receive adequate support from the PNA due to a variety of constraints placed upon the Palestinian government. That the PNA is only able to build schools in 5% the Jordan Valley means that a high number of Palestinian children are denied their basic right to education, or are forced to travel many kilometers by foot over dangerous terrain to attend school. While the PNA has received a small number of permits to build schools in Area C, the majority of schools are extremely dangerous and not conducive for learning.(89)

Approximately 10,000 children living in Area C started the 2011/12 school year learning in tents, caravans, or tin shacks which lack protection from the heat and cold. Furthermore, nearly a third of Area C schools lack adequate water and sanitation facilities. In addition, at least 23 schools serving 2,250 children in Area C have pending stop-work or demolition orders.(90)

A shortage of local teachers in the Jordan Valley causes a high student to teacher ratio throughout the region. Additionally, many of the teachers are either volunteers or interns from other parts of the Jordan Valley or West Bank.(91)

Due to occasional closures of checkpoints, teachers are often delayed, resulting in students suffering from an unstructured curriculum and the intermittent presence of trained professionals. Closures are sporadic and can be for a couple hours, or for the whole day. Often there are flying checkpoints set up on the road connecting Tubas and Jiftlik, hindering the many teachers who reside in Tubas.(92)

A significant reason for the dearth of Palestinian teachers is that no incentives exist to teach for Palestinian schools in the Jordan Valley, unlike in Israeli settlements. Teachers in settlements, as mentioned, make 12-20% more than teachers in Israel proper, which equates to approximately 11,000NIS/month ($2,900).(93) Meanwhile, Palestinian teachers in their first years make 2,000NIS/month ($533), or 3,300NIS/month ($880) for teachers who have over ten years experience.(94)

Palestinian schools are also poorly funded, leading to low teacher salaries and inadequate teaching materials. In fact, the budget in many schools is so low that large portions of the annual budget are dedicated to simply making copies of textbooks.(95)

Whereas the Israeli government pays the entire cost of education for its settlers, the Palestinian Authority is unable to provide the same type of support in Area C due to the restrictions of the occupation.

Construction of Homes and other structures

Palestinians in the Jordan Valley also face numerous obstacles involving the construction of private buildings. Similar to the construction of schools and water structures, Palestinians are required to attain the proper Israeli permits. Palestinians who live in Area C of the Jordan Valley risk the demolition of any structure built without a permit. This is especially true in recent years as Israeli demolitions of Palestinian structures have significantly increased.(96)

Building permits are almost impossible to obtain from the Israeli authorities; between 2000 and 2007, only 6% of requested permits were granted.(97)

As many Palestinians are unable to obtain building permits, they are forced to build houses, wells, clinics, and other essential structures illegally. Such structures soon become a target for demolition by Israel; from January 2010 to June 2011 in the Jordan Valley alone, Israeli authorities demolished 272 structures.(98)

Peace Now reported that 1,663 Palestinian structures were demolished by Israel in the Jordan Valley between 2000 and 2007.(99)

Furthermore, according to a Save the Children study conducted in 2009, 31% of Jordan Valley Palestinians have been either temporarily or permanently displaced at least once since 2000 as a direct result of Israeli military orders or house demolitions.(100)

In contrast, the Israeli settlers in the Jordan Valley have access to large swaths of land for housing and agriculture. Despite the hardships imposed on Palestinians due to Israeli restrictions on movement and water, recently Israel has doubled the land available to Israeli settlers in the Jordan Valley in addition to increasing the amount of water allocated to Israeli agriculture in the area.(101)

In contrast to the difficulties faced by Palestinians relating to permits and demolition orders, the Israeli government has facilitated settlement construction in the Jordan Valley by granting them financial assistance to ease the burden of settlement expansion. Even during the ten month “settlement freeze” spanning from December 2009 to September 2010, building continued to occur in the Jordan Valley.(102)

Movement Restrictions

Currently, approximately 58,000 Palestinians hold Jordan Valley residency, out of over 2.5 million living in the region. Only these registered residents are officially allowed to enter the Jordan Valley area north of Jericho. Other than the scattered pockets of Area A and Area B, travel for Palestinians without residency in the Jordan Valley is technically illegal. Even though the military does not typically enforce the travel laws, Palestinians who do not have residency in the Jordan Valley are required to obtain a permit from the Israeli authorities to enter the area, and another in order to travel on Road 90, the road that connects all villages to one another.(103)

Additionally, Israel controls the Palestinian population registry. Since 2000, in violation of past agreements between the PNA and Israel, it has refused to update or recognize changes in the registry made by the PNA. Thus, the Israelis have not recorded any changes in residency for Palestinians in the last 12 years, which means the ID cards of people who have moved still state a residency outside the Jordan Valley.(104)

Since approximately 95% of the Jordan Valley is under settlement or military control, Palestinian access to this land is deemed illegal. For the many Palestinians in the Jordan Valley who are Bedouin or animal herders, this is a crippling restriction and marks a blatant violation of numerous international agreements on indigenous and economic rights.(105)

Entering these areas can result in fines, detention, arrest, or confiscation of personal property by Israeli soldiers, police, or other authorities.(106)

What makes these laws especially difficult to follow is that most of these areas, including numerous minefields, are not properly demarcated. This means many Palestinians, mostly herders, who perhaps unknowingly enter these areas and are liable to be punished. Additionally, the unmarked minefields cause numerous injuries and deaths every year; 30% of those injured in Israeli minefields are children.(107)

Case Study: Fasayil and Tomer: The Limitations on Construction

The Palestinian communities of Fasayil alTahta,Fasayil al-Wusta,and Fasayil Foqa lie in the central Jordan Valley. Situated between the Israeli settlements of Tomer and Peza’el, these communities constitute the greater village of Fasayil. Overall, Fasayil has a population of approximately 2,100 Palestinians crowded onto approximately 400 dunums of land. The Oslo Accords split the village into Area B and Area C, with Fasayil al-Tahta, the largest of the three communities, designated as Area B and the other two falling under Area C. Around 1,300 Palestinians live in the Area B territory of Fasayil al-Tahta, leaving a further 800 in Fasayil al-Wusta and Fasayil al-Foqa, in Area C.

The designation of part of the village as Area C has resulted in a drastic contrast in development within the same community. Throughout Fasayil, Israeli policy greatly hinders the ability to construct and develop. As a result, many homes in Fasayil remain rudimentary structures made of tin, plastic, and mud. In many cases, Palestinian families who are unable to secure the proper permits live in temporary tents. Without the ability to freely build homes or other structures on their own land, Palestinians in Fasayil have a limited capacity to properly deal with the natural demographic growth of the community. Moreover, the Palestinian communities in Fasayil are often the target of Israeli demolitions. Such was the case on 14 June 2011, when Israeli forces demolished ten homes of Palestinian Bedouin in Fasayil al-Wusta.(i) In fact, since January 2011, there have been four waves of demolitions, in which the Israeli military has demolished 30 homes and other structures belonging to residents of Fasayil. Furthermore, the whole community has a pending demolition order which could be acted upon at any moment, leaving homeowners to endure a highly volatile living situation.(ii)

Located just south of Fasayil is the Israeli settlement of Tomer. Israeli civilians established the settlement in 1976 as a collective Moshav that specializes in the production of dates. Today, the settlement houses 320 Israeli settlers who hold municipal control over 4,500 dunums of land that surrounds their Palestinian neighbors to the north. As a Jordan Valley settlement, Tomer is a National Priority Area for Israel, entitling the settlement to valuable benefits from the Israeli government. As a result of the tax breaks, grants, and other benefits that the settlement receives, Tomer has become a flourishing community with a modern infrastructure, prosperous industries, and reliable social services.

When settlers in Tomer wish to expand and build new structures, they must only deal with civil authorities, as opposed to the myriad military and administrative obstacles that Fasayil residents face when applying for construction permits. In the cases of settlers, permits are approved immediately and in many cases facilitated by government financial backing. Within the settlement, most houses are multi-storey, well-insulated structures with gardens and pools, unlike the crowded and unstable conditions in which their Palestinian neighbors must live.

By the Numbers

Tomer:

- 20 Israel settlers have access to over 4,500 dunums, a ratio of 14 dunums per person.

- Approximately 4,100 are cultivated for agricultural usage.

Fasayil:

- 2,100 Palestinians have access to 400 dunums, a ratio of .19 dunums per person.

- None of the 400 dunums are cultivated or able to use for agriculture.

- There have been 30 demolitions since January 2011.

i- MA’AN News Agency, 10 Homes Bulldozed in Jericho Valley, 14 June 2011

ii- MA’AN Development Center Interview 22 Febrary 2012

Other services

The restrictions that are placed on Palestinian activity in the Jordan Valley also prevent the PNA from providing basic services to the Palestinians living in the area. This stands in stark comparison to the Israeli settlements in the area. While Israel actively prevents the PNA from providing basic services to the Palestinians of the Jordan Valley, Israeli settlements are thriving due to the generous hand of the Israeli government. This precarious situation has caused 36% of Palestinians to cite the lack of access to services as the main reason for wanting to move out of the Jordan Valley.(108)

Health Care

Israeli restrictions considerably limit Palestinian access to health care. The closest hospitals are located in Jericho or Nablus; the Jericho hospital is in the south of the Jordan Valley and far from many Palestinian villages while access to the Nablus hospital is severed by the Hamra checkpoint. An ambulance transporting a sick or injured Palestinian from the northern Jordan Valley cannot bring the patient directly to Nablus. Instead, at the checkpoint, the patient must be transferred from the Jordan Valley ambulance to a Nablus ambulance before continuing to the hospital.(109)

Within the Jordan Valley, there are rudimentary clinics in several of the larger villages, such as Jiftlik and Zbeidat. The doctors, mainly from Tubas, Nablus or Jericho, are only able to visit three to four days a week in Zbeidat and five days a week in Jiftlik. Yet these small clinics are inadequate for the needs of the communities. Unable to secure a permit to build a clinic in Area C, the village of Zbeidat was forced to utilize a small, broken-down building.(110)

In the Jiftlik clinic, the absence of female nurses or doctors often scares away female patients who are in need of health care. Like many other local clinics, the Jiftlik clinic does not have adequate supplies for everyday treatments while the laboratory lacks enough supplies to function more than two days a week.(111)

Moreover, the PNA is unable to cover the professional development courses that are necessary to ensure that Palestinian health professionals are adequately trained. Likewise, the Palestinian government does not provide the clinics with the proper supplies to treat the people of the Jordan Valley.(112)

Consequently, local clinics are often left without doctors, who may be held up at checkpoints, without supplies, due to inadequate funding, or both. These restrictions result in only 8% of Palestinians in the Jordan Valley saying that health services were available to them, as opposed to 66% for average West Bank Palestinians.(113)

The clinics in the settlements, on the other hand, are officially part of the Israeli health care system and are open five and a half days a week. Every clinic is supplied with the necessary equipment and proper technology to treat people for the majority of illnesses. Unlike the facility in Zbeidat, the settlers are allowed to choose the best location for their clinic, instead of turning to a dilapidated structure out of necessity. Also, unlike the Jiftlik clinic, the settler clinics have enough doctors and nurses of both genders to allow everyone to feel as comfortable as possible. Currently there is a project to create a small hospital in an area called Mifgash HaBeka’ot, between the settlements of Petza’el and Tomer in the central Jordan Valley.(114)

Although there are more Palestinians than settlers in this area, Palestinian residents will not be allowed to use this hospital, as they are not Israeli citizens.

Security

As most of the Jordan Valley is Area C, the PNA is unable to provide police and security forces for the Palestinians living under Israeli military control. As a result, over 90% of Palestinian households in the Jordan Valley said they do not feel secure in their area of residence, the vast majority citing the Israeli occupation, both military and civilian, as the main reason for their sense of insecurity.(115)

Israeli soldiers and police handle issues of settler violence, often creating an aura of immunity among settlers.(116)

Consequently, settler violence is a major threat to the Palestinian people. Even in the Jordan Valley, where settler-Palestinian tension is generally lower, there are frequently recurring reports of settler violence and intimidation. Settlers from the Maskiot settlement, who were given a hilltop above the Palestinian herding community of Ein al-Hilwe, are a perfect example of the reoccurring settler violence that plagues the Palestinian people and the lack of justice and accountability. In the past 18 months, settlers from Maskiot, with military and police protection, have stolen 200 dunums of grazing land from the Palestinian herding community below.(117)

The settlers also have repeatedly stolen animals belonging to the Palestinians and brought them to the settlement for their own use, or in other cases simply let them roam free.(118)

The security situation for Palestinians is, of course, completely different than for Israeli settlers. Every settlement has a military patrol for the surrounding area, a military guard at the entrance, a civilian police force, a heavily fortified fence, spotlights in the settlement, as well as a “Minuteman Rapid Response Team.”(119)

The extensive security precautions of the Israeli government in the settlements of the Jordan Valley have created a great sense of security among Israeli settlers while Palestinians are left without any protection, thus fostering a general feeling of insecurity.(120)

Case Study: Recreational Space for Children in Marj Na’ajeh

The Palestinian village of Marj Na’ajeh is located in the northern Jordan Valley and is home to approximately 800 Palestinians. The 800 residents live on 224 dunums of Area B land in addition to 30 dunums of Area C land. As the village lacks a preschool, the children of Marj Na’ajeh cannot attend formal school until the ages of 6 or 7, leaving those younger without proper, safe play areas or important early childhood education. Many resort to playing in the street or in the playground of the school, which closes around 3:30pm.

A very small, basic play area does exist on a plot of Area C land. Unfortunately, in 2009 the community appropriated the adjacent field for burning waste due to the municipality’s inability to collect trash on a regular basis. Marj Na’ajeh suffers from extremely high rates of unemployment, reaching 80% among women and 40% among men, which leaves most residents without the dispensable income to pay for trash collection over an extended period of time.i The trash burning halted ten months ago, but the after-effects of the practice have left the playground unsuitable for recreation.

The Israeli settlement of Ma’ale Ephraim is located in the central Jordan Valley, housing approximately 1,400 settlers and covering over 4,000 dunums of land. The settlement enjoys significant public services and outdoor areas, including a large grassy play area for children. Safe slides and swings are a sharp contrast to the dangerous and broken outdoor toys that rest on broken glass, dirt and rocks. Healthy trees provide shade for Israeli settlers relaxing on new, comfortable benches, allowing settler parents comfort while watching their children play. In Marj Na’ejeh, Palestinian parents do not allow their children to enter the ‘play area’ as it is far too dangerous for use.

“I play football in the play area because there is nothing else, I wish there were more play areas here.” Muhammad, six years old.

“If there was a good and safe playground I would use it, but there isn’t so I play in the area outside of my house.” Asma, six years old

i MA’AN Development Center Interview 12 February 2012

Communication and electrical networks

Israel tightly regulates all communication and electrical networks in the Jordan Valley. This situation forces many Palestinians to buy electricity or communication materials, such as phone and internet lines, from Israel. Moreover, Palestinian companies such as Jawwal, PalTel, Hadara, Wataniya, etc. are systematically blocked from offering communication ser vices to Palestinians or even Israeli settlers in the Jordan Valley. Although Palestinian communication industries have attempted on numerous occasions to establish a presence in the Jordan Valley, their requests have been repeatedly rejected by Israel. The last time this was attempted was in late October 2010 when Jawwal and Wataniya tried to build cell phone towers in the village of Ein al Beida. Israel refused the application, even after a family offered to have the towers built on top of their house so the companies could avoid Area C. The request was still denied.(121)

Employment

Due to the massive and harsh restrictions imposed on the Palestinian population in the Jordan Valley, there are very few opportunities for economic and social development. The expansion of military areas and settlements, in addition to other movement restrictions, has greatly reduced the ability of Palestinians to access the abundant cultivatable agricultural and grazing land. Consequently, the livelihoods of many Palestinians have been eliminated. Herders are often forced to sell their entire flock in order to pay for fodder, or farmers are unable to keep prices competitively low because of the need to purchase high-priced water.(122)

For those Palestinians who are not forced to leave the Jordan Valley, the only means of income often becomes employment in Israeli settlements. To exacerbate their desperate situation, Palestinians who do work in settlements earn less than the Israeli minimum wage of 200 NIS per day. The highest wage that has been reported by a Palestinian worker in a Jordan Valley settlement has been 100 NIS per day, with the lowest being 50 NIS for a full day ’s work.(123)

Moreover, though Israeli settlers claim that Palestinian workers are given health care and pension benefits, as required by Israeli law, there have been no reports of Palestinians confirming this claim in the inter views conducted for this publication.(124)

Unlike their Israeli counterparts, Palestinians, working in settlements or in Palestinian enterprises, do not receive employment benefits.(125)

Conclusion

Since shortly after the 1967 war, the Israeli government has followed a clear and deliberate policy to encourage Israeli Jewish citizens to relocate in the occupied Palestinian territories. Although the government strategy has evolved, the overall result has stayed the same: the expansion of Israeli control over the most territory possible while maintaining responsibility for the least number of Palestinians possible. The confiscation of Palestinian land for military and civilian use, in addition to the exhaustive restrictions on nearly every facet of Palestinian life, has resulted in the exodus of over 300,000 Palestinians from the strategically and economically important Jordan Valley.(126)

Since the beginning of the occupation, support from the Israeli government has allowed Israeli settlers to both thrive in and expand on their settlements.

The Jordan Valley settlements are among the most subsidized settlements in the occupied Palestinian territories. In order to maintain their viability and competitive edge, the Israeli government must heavily invest in their infrastructure, public and private institutions, and essential services. Private companies receive substantial compensation for bringing business to the occupied territories while individual families are qualified to receive free land, housing, and education simply by moving to Palestine. As a settler remarked when discussing how the policy changes with each new government (the current one being not as favorable), “it is still cheaper to build a house, cheaper than anywhere else.”(127)

The Israeli government spends hundreds of millions of dollars on the Jordan Valley settlements while denying the Palestinian people in the same region the most basic of rights and refusing to provide them with essential social services, as dictated by international law.(128)

Indeed, the illegal settlements throughout the West Bank, and in the Jordan Valley in particular, can and should be condemned for many reasons. The modern and expanding settlements in the West Bank vary little from their community counterparts in Israel proper, despite being clearly and unquestionably against international law. Likewise, the treatment of Palestinians by the Israeli military in the West Bank is abhorrent. These two Israeli policies, taken separately, give reason enough to condemn Israel. Yet it is in the comparison of the marginalized Palestinian communities and the privileged Israeli settlements that one can really see the institutionalized racism that fundamentally influences Israel’s settlement policy. The results of Israeli discrimination can be seen clearly in every Palestinian village that is denied the right to build a school, a well, or a medical clinic.

The shocking differences between the quality of life in Palestinian villages and Israeli settlements in the Jordan Valley are obvious manifestations of the decades-old Israeli policy to remove Palestinians from their own land. By refusing to care for the Palestinians under military rule while also refusing to allow the PNA access to these vulnerable communities, Israel is forcing Palestinians to depopulate an important piece of land that is essential to the viability of a future Palestinian state. At the same time, the Israeli government has ensured the viability and sustainability of the settlements in the Jordan Valley by directly subsidizing their infrastructure, employment, and social services. All of this brings one to the conclusion that the State of Israel, through its settlement enterprise, is actively protecting the extravagant lifestyle of Israeli Jews in the occupied territories at the expense of the basic human rights of Palestinians. Only a complete reversal of policy with appropriate reparations for lost economic activity and community services will begin to adequately address the gross injustice that has continued for over forty years.

References

- The conditions of Oslo stipulated that Area C would eventually fall under Palestinian authority, but that outcome was never realized.

- Segal, Rafi, A Civilian Occupation; The Politics of Israeli Architecture, 2002 19-26

- The first planned area of settlement was what became the Gush Etzion bloc, south of Jerusalem, which currently houses 22 settlements and 70,000 settlers. Another case of government sponsored and planned settlement is of the settlement Kiryat Arba, adjacent to Hebron. Gazit, Shlomo, Trapped Fools: Thirty Years of Israeli Policy in the Territories, 2003 pg. 240-255

- Gazit, Shlomo, Trapped Fools: Thirty Years of Israeli Policy in the Territories, 2003 pg. 252

- Gazit, Shlomo, Trapped Fools: Thirty Years of Israeli Policy in the Territories, 2003 pg. 250

- Nahal settlements were military outposts in the West Bank, many of which converted to civilian use within a couple years. In many instances, the soldiers themselves, after their service, never left the outposts and had their family move to it, hence becoming a full-fledged civilian settlement.

- Gazit, Shlomo, Trapped Fools: Thirty Years of Israeli Policy in the Territories, 2003 pg. 251-2

- Shapira, Anita Yigal Allon: Native Son 2008 pg. 312

- Gazit, Shlomo, Trapped Fools: Thirty Years of Israeli Policy in the Territories, 2003 pg. 241

- For example, the recent negotiations between the Palestinian Authority and Israel proposed the annexation of settlement blocs around Jerusalem due to the demographic weight of Israeli Jews living in these settlements. Israeli negotiators constantly refer to “Jewish neighbourhoods of East Jerusalem going to Israel, and Palestinian neighborhoods going to the future Palestine.” This situation is also used for large settlement blocs such as Gush Etzion, Ariel, and Qedumim and that their evacuation or falling under Palestinian sovereignty is impossible. Swisher, Clayton The Palestine Papers, 2011

- Gazit, Shlomo, Trapped Fools: Thirty Years of Israeli Policy in the Territories, 2003 pg. 242

- Efrat, Elisha, The West Bank and Gaza Strip; A Geography of Occupation and Disengagement, 2005 pg. 24

- MA’AN Development Center Restricted Access, 2011 pg.10, B’tselem Dispossession and Exploitation; Israel’s Policy in the Jordan Valley and Northern Dead Sea (updated edition), 2011 pg. 57-9

- It is difficult to point to an exact number of Palestinians that were forced out of the Jordan Valley due to the 1967 war. Shlomo Gazit notes that at least 70,000 refugees from the 1948 war that were located in refugee camps relocated during the war. UNRWA notes that 30,000 Palestinian refugees from the ‘Aqbat Jaber refugee camp and ‘most’ of the Palestinians from the ‘Ein a-Sultan refugee camp (20,000) also fled to Jordan. Raja Shehadeh estimates that 100,000 Palestinian refugees left the Jordan Valley in 1967 while an Israeli source, according to B’TSelem, estimates 200,000 refugees were forced out. See: B’tselem, Dispossession and Exploitation; Israel’s Policy in the Jordan Valley and Northern Dead Sea, 2011 pg. 10, footnote 11. Moreover, according to the European Union, there were between 200,000 and 320,000 Palestinians living in the Jordan Valley [see: EU Observer, EU Ministers Look to Israeli Grab of Palestinian Farmland, 2012, available at http://euobserver.com/24/114879.] The 1967 Israeli census, conducted after the war, revealed that the Palestinian population of the Jordan Valley was no more than 15,000 [See: Elisha Efrat, The West Bank and the Gaza Strip, 2005, pg. 25.]

- Efrat, Elisha, The West Bank and Gaza Strip; A Geography of Occupation and Disengagement, 2005 pg. 34

- Kibbutzim are collective settlements where the wealth of the community is distributed equally among all its members. Moshavim are settlements where the agreed upon features are communal but others, such as farms are privately owned and the profit goes to the owner of the farm. Most of the settlements in the Jordan Valley are, or started off as, Kibbutzim or Moshavim.

- Efrat, Elisha, The West Bank and Gaza Strip; A Geography of Occupation and Disengagement, 2005 pg. 34

- Efrat, Elisha, The West Bank and Gaza Strip; A Geography of Occupation and Disengagement, 2005 pg. 95

- Efrat, Elisha, The West Bank and Gaza Strip; A Geography of Occupation and Disengagement, 2005 pg. 36

- This body, created by the Israeli government after the war is meant to be “responsible for the government and abandoned property in the West Bank. The office was established in 1967 with the objective of managing government owned lands, lands deserted by Arabs who left the region, and Jewish-owned lands purchased during the 1930’s” as according to their own website. http://www.cogat.idf.il/1330-en/Cogat.aspx Accessed 5 February 2012. In fact this body has been used as a method to confiscate large areas of the West Bank with a veil of legitimacy, which continues to this day.

- Efrat, Elisha, The West Bank and Gaza Strip; A Geography of Occupation and Disengagement, 2005 pg. 93-5, Troen, Ilan, Imaging Zion: Dreams, Designs, and Realities in a Century of Jewish Settlement, 2003 pg. 62-84

- B’tselem, Dispossession and Exploitation; Israel’s Policy in the Jordan Valley and Northern Dead Sea, 2011 pg. 13

- Efrat, Elisha, The West Bank and Gaza Strip; A Geography of Occupation and Disengagement, 2005 pg. 38

- Jerusalem Post, 70 West Bank Settlements on National Priority List, 29 January 2012

- B’tselem, By Hook and By Crook, 2010 pg. 37

- B’tselem, By Hook and By Crook, 2010 pg. 38

- Jerusalem Post, 70 West Bank Settlements on National Priority List, 29 January 2012.

- B’tselem, By Hook and By Crook, 2010 pg. 39

- As an example, Natan Sharansky was the housing minister from 2001-3 and invested much time and money into further developing Jordan Valley settlements, including offering subsidized mortgages of up to 95% for new houses in Jordan Valley settlements.

- In addition to the special conditions that only settlements can meet, the legislation provided more money to Jewish settlements in the West Bank than to Palestinian communities in Israel. B’tselem By Hook and By Crook pg. 39

- MA’AN Development Center Interviews conducted 5, 11, 18, and 25 December 2011 in Jordan Valley settlements. See also: Adalah, On the Israeli Government’s New Decision Classifying Communities as National Priority Areas, 2010 pg. 8-9

- B’tselem, By Hook and By Crook, 2010 pg. 41-2

- B’tselem, By Hook and By Crook, 2010 pg. 44

- MA’AN Development Center Interview, 5 December 2011

- Five regional councils represent settlements that are located in the Jordan Valley.

- MA’AN Development Center Interview, 11 December 2011

- MA’AN Development Center Interview, 11 December 2011

- MA’AN Development Center, Bankrolling Colonialism, 2010 pg. 32-3

- Efrat, Elisha, The West Bank and Gaza Strip; A Geography of Occupation and Disengagement, 2005 pg. 39

- Tilley, Virginia, The One-State Solution, 2005 pg. 43-4

- Tilley, Virginia The One State Solution, 2005 pg. 43

- B’tselem, By Hook and By Crook, 2010 pg. 40-1

- MA’AN Development Center Interview 11 December2011. They also mentioned that until the mid 1990s, the government was building the houses as cheaply as possible for settlers.

- MA’AN Development Center Interview, 5 December 2011

- Seattle Times, Lawsuit Brings Murky West Bank Land Deals to Light, 20 June 2009

- Seattle Times, Lawsuit Brings Murky West Bank Land Deals to Light, 20 June 2009

- Human Rights Watch, Separate and Unequal, 2010 pg. 55

- This includes things such as olive presses, vineyards, and small dairies. See: B’tselem, By Hook and By Crook, 2010 pg. 44.

- Invest in Israel” program website as part of the Israeli Ministry of Industry, Trade, and Labor, accessed 28 December 2011, http://www.investinisrael.gov.il/NR/exeres/07596533-A5AE-4797-B2C4-196EFF11E0A6.htm

- While specific government support was not detailed, settlers repeatedly confirmed in interviews that the government helps settlements circumvent the boycott. See: MA’AN Development Center Interview, 5 December 2011, and MA’AN Development Center Interview 18 December 2011.

- B’tselem, By Hook and By Crook, 2010 pg. 43

- Israeli Ministry of Industry, Trade and Labor’s Website in English, Accessed 28 December 2011, http://www.tamas.gov.il/NR/exeres/52818A8A-8458-45D0-A84ACA7FE4381ACF.htm

- Some qualifications do exist, such as having five workers in the company and a minimum wage of either 3,850NIS or 5,500 NIS depending on the area. See: “Invest in Israel” program website as part of the Israeli Ministry of Industry, Trade, and Labor, Accessed 28 December 2011, http://www.investinisrael.gov.il/NR/exeres/EECEBB1D866C-4D5D-9FB4-593C556622D7.htm,

- B’tselem, By Hook and By Crook, 2010 pg. 44

- On average, settlers during this time paid 40% less than metropolitan Israelis and 33% less than Israelis living in development towns in Israel. See: B’tselem, By Hook and By Crook, 2010 pg. 44, Adva Center, Governmental Priority in Funding Communities: 2000-6

- “Invest in Israel” program website as part of the Israeli Ministry of Industry, Trade, and Labor, Accessed 29 December 2011, http://www.investinisrael.gov.il/NR/exeres/669EBEB2-81A5-48E2-8255-65E810060D9B.htm

- B’tselem, By Hook and By Crook, 2010 pg. 42

- This is almost double the national average for Israel, which is 12.9%. See: B’tselem, By Hook and By Crook, 2010 pg. 42.

- MA’AN Development Center Interview, 5 December 2011

- B’tselem, By Hook and By Crook, 2010 pg. 42

- MA’AN Development Center Interview, 5 December 2011

- MA’AN Development Center Interview, 5 December 2011

- B’tselem, Dispossession and Exploitation; Israel’s Policy in the Jordan Valley and Northern Dead Sea, 2011 pg. 40, in addition, this number is one-fourth the world average according to World Bank standards.

- MA’AN Development Center Interview, 9 August 2011

- MA’AN Development Center Interview, 5 December 2011, 11 December 2011

- B’tselem, Dispossession and Exploitation; Israel’s Policy in the Jordan Valley and Northern Dead Sea, 2011 pg. 24

- B’tselem, Dispossession and Exploitation; Israel’s Policy in the Jordan Valley and Northern Dead Sea, 2011 pg. 39

- MA’AN Development Center Interview, 5 December 2011

- MA’AN Development Center Interview, 5 December 2011

- MA’AN Development Center Interview, 11 December 2011

- MA’AN Development Center Interview, 11 December 2011

- Save the Children, Jordan Valley, 2009

- MA’AN Development Center Interview 11 December 2011

- Save the Children, Jordan Valley, 2009

- MA’AN Development Center, Draining Away, 2009 pg. 11

- Diakonia, Israel’s Administrative Destruction of Cisterns in Area C of the West Bank, 2011

- MA’AN Development Center, Restricted Access, 2011 pg. 4

- Save the Children, Jordan Valley, 2009

- MA’AN Development Center Interview 5 December 2011

- Center for Economic and Social Rights, Thirsting for Justice, 2003 pg. 15

- As cited in: Human Rights Watch, Separate and Unequal, 2010 pg. 73

- Human Rights Watch, Separate and Unequal, 2010 pg 73

- Save the Children, Jordan Valley

- MA’AN Development Center, Draining Away, 2011 pg. 21

- B’tselem, Dispossession and Exploitation; Israel’s Policy in the Jordan Valley and Northern Dead Sea (updated edition), 2011 pg. 40

- B’tselem, Dispossession and Exploitation; Israel’s Policy in the Jordan Valley and Northern Dead Sea (updated edition), 2011 pg. 24

- World Health Organization Domestic Water Quantity, Service Level, and Health, 2003

- B’tselem Presentation, Taking Control of Water Sources in the Jordan Valley, Accessed 3 January 2012, http://www.btselem.org/presentations/jordan_valley/water_eng.htm

- The story of the school in Jiftlik is a prime example of the inability of the PNA to deliver goods or services to the Palestinians who live in Area C of the Jordan Valley. The first school in Jiftlik built was built out of tents as the nearest school was cut off from the village by the Hamra checkpoint. The Israeli army demolished the school three times, only to see the Palestinians rebuild the modest tent structures. After the third demolition, the situation in Jiftlik garnered international attention. Pressure from the French and Malaysian governments resulted in Israel issuing a permit to build a permanent school in the village. See: Brighton Jordan Valley Solidarity, Al Jiftlik – a Jordan Valley Success Story. Accessed 22 February 2012, http://www.brightonpalestine.org/2011/node/85; and International Solidarity Movement, Israel Plans House Demolitions in Jiftlik. Accessed 22 February 2012,

- This is out of a total Area C population of 150,000. Since about 25% of the Palestinian population is of school-age, it means that 25% of Area C students are submitted to these conditions. See: Save the Children, Children’s Right to Education in Armed Conflict, 2011

- MA’AN Development Center Interview 3 February 2012

- MA’AN Development Center Interview 29 January 2011