Al Jazeera: How Israel engages in ‘water apartheid’

First published by Mersiha Gadzo on Al Jazeera 21st October 2017

Meanwhile, neighbouring settlements consume copious amounts of water. They grow produce, such as bananas, requiring large amounts of water, which is mostly pumped from wells in the occupied West Bank, and they export a rich variety of fruits, vegetables, flowers and spices to Europe and the United States.

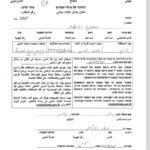

In the village of Ein al-Beida, barbed wire divides a field in two.

On one side are rows of orange trees covered in lush green leaves, grown by Israeli settlers from a nearby illegal settlement; on the other is barren land allocated for Palestinians, where nothing grows except stiff stalks of yellow grass, long dried out due to the lack of water.

Farmers in Ein al-Beida, one of the few villages in the Jordan Valley that is connected to the water grid, last month staged a peaceful protest after Israeli authorities cut their water for more than a week.

Israeli authorities eventually turned their water back on, but locals say the amount is now less than half of the 240 cubic metres an hour that they received before the protest.

“They gave us the excuse that there’s not enough water underground,” farmer Mahdi Foqaha told Al Jazeera. “In reality, Israel doesn’t want us to live here any more … We just want the Israelis to let us extract our own water.”

Many Palestinians who depend on agriculture for a living try to install water pipes and connect to the water network on their own. Doing so without an Israeli permit, however, is deemed “illegal” and puts them at risk of having these makeshift connections demolished.

Only 1.5 percent of Palestinian building permit applications in Israeli-administered Area C of the occupied West Bank were approved between 2010 and 2014. Consequently, Palestinians have no choice but to build without a permit, even if it is a simple rainwater tank on private property.

“In [the neighbouring village] Bardala, Israelis decreased the water to 170 cubic metres for the whole village; people were forced to connect to the water ‘illegally,'” Foqaha said. “We want to live. What else can we do?”

However, the Israelis discovered the illegal connection “and punished the whole area by decreasing and cutting our water”, Foqaha added.

The Israeli government did not respond to Al Jazeera’s request for comment on the matter.

Choking water supply

Following the 1967 war and Israel’s military occupation of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, one of Israel’s first acts was to declare all water resources to be under Israeli military control. In order for Palestinians to build wells, repair pipes or develop irrigation networks, they had to obtain Israeli-issued permits, which are scarcely granted.

As a result, Palestinians often have their water tanks confiscated and pipes cut by Israeli authorities.

Palestinian farmers in the Jordan Valley recall a time before 1967, when their families freely used the water from springs that ran through their villages and watered their crops with canals. Their fathers grew citrus fruit and bananas; water was plentiful.

After the 1967 war, the Israeli government confiscated land where the main spring flowed in Bardala and diverted the water to nearby agricultural settlements. Mekorot, Israel’s national water company, dug deep into the mountain aquifer, and by the end of the 1970s, Israel had extracted so much water that the springs in Bardala and Ein al-Beida had dried up.

Since groundwater sources have been depleted by Israeli-owned wells, Palestinians have resorted to buying their own water back from Mekorot at a high cost.

“The Israelis dug underground, conducted experiments and found out that this whole area is full of water,” Foqaha said.

“We used to have five, six central wells, but the Israelis took these wells from us and drained the water … All of us farmers [in Ein al-Beida] consume the same amount of water as one settler in [the illegal settlement] Mehola.”

Discriminatory policies

Water may be scarce for Palestinians, but it is not for Israeli settlers. The difference in consumption is stark: According to EWASH, a coalition of 30 NGOs, settlers in the Jordan Valley consume 81 times more water per capita than Palestinians in the West Bank.

Israel’s policies regarding water distribution amount to “water apartheid”, according to the human rights organisation al-Haq.

“Contrary to popular belief, water is not, and has not been, scarce in the region,” al-Haq noted in a 2013 report titled Water For One People Only.

“The level of unrestricted access to water enjoyed by those residing in Israel and Israeli settlers demonstrates that resources are plentiful, and that the lack of sufficient water for Palestinians is a direct result of Israel’s discriminatory policies in water management.

“Mekorot routinely reduces Palestinian supply – sometimes by as much as 50 percent – during the summer months in order to meet consumption needs in the settlements,” the report added.

The water cuts are not limited to areas under Israeli control. According to residents in Nablus in Area A, which is under Palestinian Authority (PA) control, water shortages reached a new peak this past summer, with water cuts lasting for as long as two weeks.

‘End oppression’

Farmer Ibrahim Kassab from the village of Jiftlik told Al Jazeera that half of his profits were spent on buying water for his crops. About 90 percent of his water supply is bought from Mekorot, and only 10 percent comes from the spring.

“Everyone here is thinking the same thing – to quit farming,” Kassab said, noting that half of the farmers in the village have already abandoned their farms and picked up jobs as labourers elsewhere.

More than 10 percent of the Palestinian GDP depends on agriculture, yet only 10 percent of the land is irrigated. In contrast, agriculture in Israel accounts for three percent of its GDP, but more than 50 percent of the land is irrigated.

“Anything that’s green is Israeli; anything that’s dry and yellow is Palestinian,” Ein al-Beida farmer Hussein Foqaha told Al Jazeera.

Farmers have nowhere to turn for help. Unable to extract their own water, their peaceful protest achieved little.

The head of their local council has reached out to the mayor of the nearest town, Tubas, to request water from the PA, but nothing has been achieved so far.

“At least we have water to drink now,” Muntasir Foqaha, another villager from Ein al-Beida, said wryly, commenting on the protest last month. “We just want the oppression from Israelis to stop.”