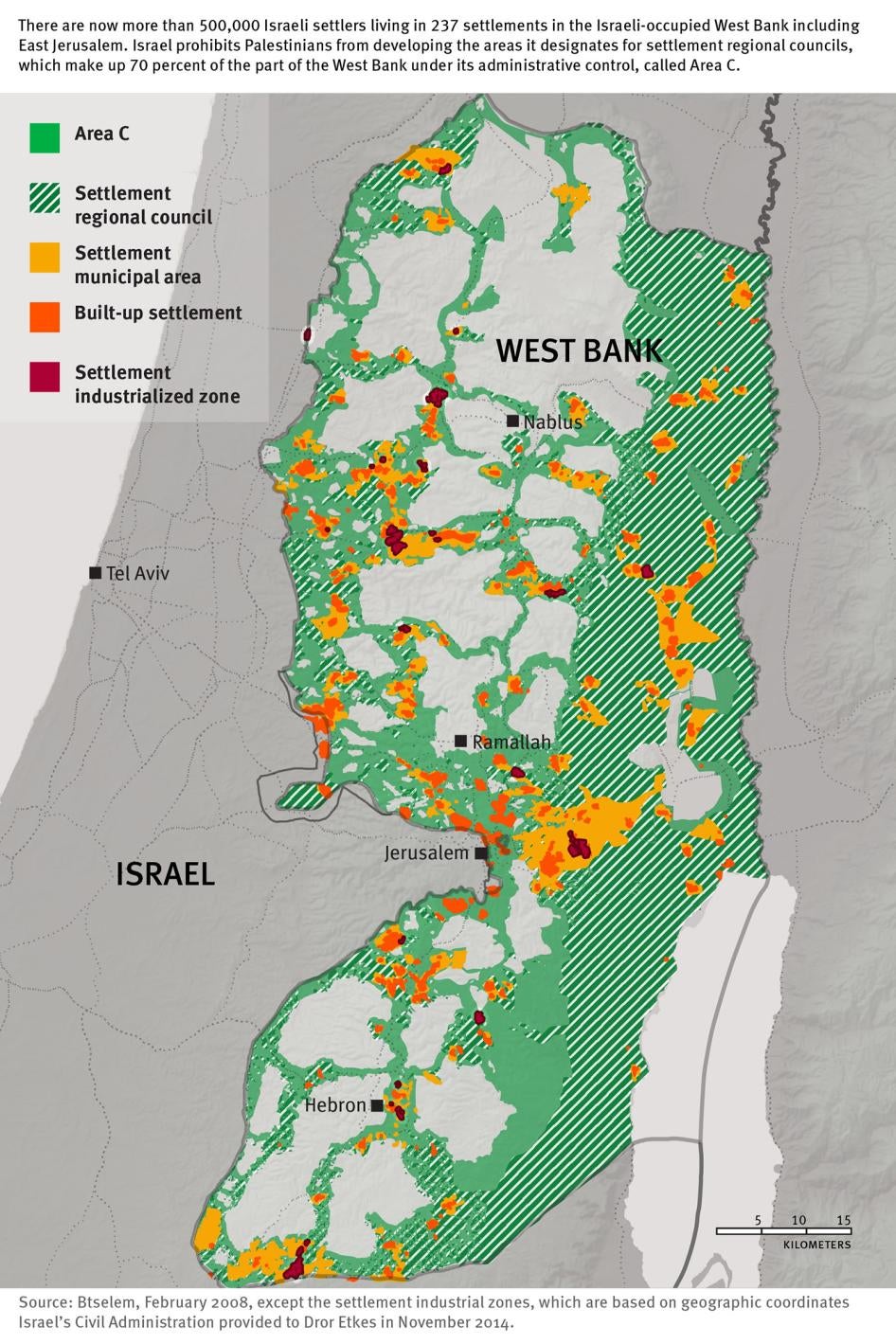

Human Rights Watch: Occupation Inc.

On 19th January 2016 Human Rights Watch (HRW) published a report entitled “Occupation, Inc.“, an extensive piece of research documenting the Israeli settlement economy across the occupied West Bank and East Jerusalem. The report investigates how Israel is extending its control of the occupied Palestinian territories through the spiralling development of industrial zones and the illegal seizure of agricultural land.

Focussing in part on the Jordan Valley, the abysmal conditions of Palestinian workers in settlement agriculture are exposed. A case study on waste management also shows how a landfill site located within the Jordan Valley exclusively services settlements including Ariel, Barkan, and cities within Israel. This is to the severe detriment of the Palestinian community (see pages 81 – 84 and Annex 1, pages 108 – 111).

Recognising settlement construction as a clear breach of international law, HRW calls on businesses to withdraw from the settlement economy. It also calls on Israel to dismantle all settlements, end discrimination and restrictions on Palestinian development, and end the system of incentives for Israeli and international businesses operating right across the occupied West Bank. The report can be accessed here in pdf format and is reproduced below. It is also available in Arabic and Hebrew.

Occupation, Inc.

Published by Human Rights Watch, January 19th 2016

How Settlement Businesses Contribute to Israel’s Violations of Palestinian Rights

Summary

Almost immediately after Israel’s military occupation of the West Bank in June 1967, the Israeli government began establishing settlements in the occupied Palestinian territories. From the outset, private businesses have been involved in Israel’s settlement policies, benefiting from and contributing to them. This report details the ways in which Israeli and international businesses have helped to build, finance, service, and market settlement communities. In many cases, businesses are “settlers” themselves, drawn to settlements in part by low rents, favorable tax rates, government subsidies, and access to cheap Palestinian labor.[1]

In fact, the physical footprint of Israeli business activity in the West Bank is larger than that of residential settlements. In addition to commercial centers inside of settlements, there are approximately 20 Israeli-administered industrial zones in the West Bank covering about 1,365 hectares, and Israeli settlers oversee the cultivation of 9,300 hectares of agricultural land. In comparison, the built-up area of residential settlements covers 6,000 hectares (although their municipal borders encompass a much larger area).

Israeli settlements in the West Bank violate the laws of occupation. The Fourth Geneva Convention prohibits an occupying power from transferring its citizens into the territory it occupies and from transferring or displacing the population of an occupied territory within or outside the territory. The Rome Statute, the founding treaty of the International Criminal Court, establishes the court’s jurisdiction over war crimes including the crimes of transfer of parts of the civilian population of an occupying power into an occupied territory, and the forcible transfer of the population of an occupied territory. The ICC has jurisdiction over crimes committed in or from the territory of the State of Palestine, now an ICC member, beginning in June 13, 2014, the date designated by Palestine in a declaration accompanying its accession.

Israel’s confiscation of land, water, and other natural resources for the benefit of settlements and residents of Israel also violate the Hague Regulations of 1907, which prohibit an occupying power from expropriating the resources of occupied territory for its own benefit. In addition, Israel’s settlement project violates international human rights law, in particular, Israel’s discriminatory policies against Palestinians that govern virtually every aspect of life in the area of the West Bank under Israel’s exclusive control, known as Area C, and that forcibly displace Palestinians while encouraging the growth of Jewish settlements.

As documented in this report, it is Human Rights Watch’s view that by virtue of doing business in or with settlements or settlement businesses, companies contribute to one or more of these violations of international humanitarian law and human rights abuses. Settlement businesses depend on and benefit from Israel’s unlawful confiscation of Palestinian land and other resources, and facilitate the functioning and growth of settlements. Settlement-related activities also directly benefit from Israel’s discriminatory policies in planning and zoning, the allocation of land, natural resources, financial incentives, and access to utilities and infrastructure. These policies result in the forced displacement of Palestinians and place Palestinians at an enormous disadvantage in comparison with settlers. Israel’s discriminatory restrictions on Palestinians have harmed the Palestinian economy and left many Palestinians dependent on jobs in settlements—a dependency that settlement proponents then cite to justify settlement businesses.

Following international standards articulated in the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, businesses are expected to undertake human rights due diligence to identify and mitigate contributions to human rights violations of not only their own activities but also activities to which they are directly linked by their business relationships. They are also expected to take effective steps to avoid or mitigate potential human rights harms—and to consider ending business activity where severe negative human rights consequences cannot be avoided or mitigated.

Based on the findings of this report, it is Human Rights Watch’s view that any adequate due diligence would show that business activities taking place in or in contract with Israeli settlements or settlement businesses contribute to rights abuses, and that businesses cannot mitigate or avoid contributing to these abuses so long as they engage in such activities. In Human Rights Watch’s view, the context of human rights abuse to which settlement business activity contributes is so pervasive and severe that businesses should cease carrying out activities inside or for the benefit of settlements, such as building housing units or infrastructure, or providing waste removal and landfill services. They should also stop financing, administering, trading with or otherwise supporting settlements or settlement-related activities and infrastructure.

Human Rights Watch is not calling for a consumer boycott of settlement companies, but rather for businesses to comply with their own human rights responsibilities by ceasing settlement-related activities. Moreover, consumers should have the information they need, such as where products are from, to make informed decisions.

This report uses illustrative case studies to highlight four key areas where, in Human Rights Watch’s view, settlement companies contribute to and benefit from violations of international humanitarian and human rights law: discrimination; land confiscations and restrictions; supporting settlement infrastructure; and labor abuses. These case studies are not necessarily the worst examples of settlement businesses, but demonstrate how businesses operating in settlements are inextricably tied to one or more of these abuses.

How Businesses Contribute to and Benefit from Discrimination

Israel operates a two-tiered system in the West Bank that provides preferential treatment to Jewish Israeli settlers while imposing harsh conditions on Palestinians. Israeli courts apply Israeli civil law to settlers, affording them legal protections, rights and benefits not enjoyed by their Palestinian neighbors who are subject to Israeli military law, even though under international humanitarian law, military law governs the occupied territories regardless of citizenship. Israel’s privileged treatment of settlers extends to virtually every aspect of life in the West Bank. On the one hand, Israel provides settlers, and in many cases settlement businesses, with land, water infrastructure, resources, and financial incentives to encourage the growth of settlements. On the other hand, Israel confiscates Palestinian land, forcibly displaces Palestinians, restricts their freedom of movement, precludes them from building in all but 1 percent of the area of the West Bank under Israeli administrative control, and strictly limits their access to water and electricity.

In 2010, Human Rights Watch published a report, Separate and Unequal, documenting Israel’s systematic discrimination against Palestinians in favor of settlers. The report found that the impact of these policies on Palestinians at times amounts to forcible transfer of the population living under occupation, since many Palestinians who are unable to build a home or earn a living are effectively forced to move to areas under Palestinian Authority control or to emigrate entirely out of the West Bank. This new report builds on Human Rights Watch’s previous findings and considers the ways in which settlement businesses are deeply bound up with Israel’s discriminatory policies.

By virtue of facilitating the settlement regime, settlement businesses, in Human Rights Watch’s view, contribute to the discriminatory system that Israel operates for the benefit of settlements. These businesses also directly benefit from these policies in myriad ways. The report describes two such ways. One is the financial and regulatory incentives that the Israeli government provides to settlement businesses, but not to local Palestinian businesses, in order to encourage the economic development of settlements. The other is the discriminatory way that the Civil Administration, the unit in the Israeli military responsible for civilian affairs in the West Bank, issues permits for the construction and operation of settlement companies, often on land confiscated or expropriated from Palestinians in violation of international humanitarian law, while severely restricting such permits for Palestinian businesses. It is therefore Human Rights Watch’s view that businesses operating in or with settlements are inextricably linked to, and benefit from, Israel’s privileged and discriminatory treatment of settlements at the expense of Palestinians.

As an illustrative example, the report contrasts the operating conditions of a quarry in the West Bank owned and operated by a European company, to the operating conditions of Palestinian-owned quarries in the West Bank town of Beit Fajar. Whereas Israel issued a permit to the European company to operate the quarry on an area of land that Israel declared belongs to the state, Israel has refused to issue permits for nearly all of the 40 or so Beit Fajar quarries, or for almost any other Palestinian-owned quarry in the area of the West Bank under Israel’s administrative control. The World Bank estimates that Israel’s virtual ban on issuing Palestinians permits for quarries costs the Palestinian economy at least US$241 million per year. Yet Israel licenses eleven settlement quarries in the West Bank despite this exploitation of resources in occupied territory violating international humanitarian law.

Article 55 of the Hague Regulations of 1907 makes occupied property subject to the laws of usufruct. The generally accepted interpretation of these rules permits an occupying power to appropriate the resources of the occupied territory only for the benefit of the protected population or if justified by military necessity. Yet the settlement quarries pay fees to settlement municipalities and the Civil Administration, which cannot be said to benefit the Palestinian people, and sell 94 percent of the materials they produce to Israel or Israeli settlements, in violation of these laws.

How Businesses Contribute to and Benefit from Land Confiscation and Restrictions

This report also describes how settlement businesses depend on, contribute to, and benefit from Israel’s unlawful confiscation of and restrictions on Palestinian land for the benefit of settlements. Some settlement businesses operate in residential settlements, or provide services to them, while others operate in “industrial zones” specially built for settlement businesses.

Such businesses depend on Israel’s unlawful confiscation of Palestinian land to build the settlements in the first place. Based on the findings of the report, it is Human Rights Watch’s view that by facilitating settlements’ residential development, these businesses also contribute to the further confiscation of Palestinian land, restrictions on Palestinian access to their lands, and their forced displacement from these lands. The report highlights the case of Ariel, a settlement Israel first established in 1978. The 4,615 dunams (462 hectares) of land on which Ariel was initially built was seized by military order ostensibly for security purposes. In the decades since, Israel has built three security fences around the settlement, each time encompassing hundreds more dunams of privately owned Palestinian agricultural land.

The report examines two illustrative case studies—a bank and real estate agency active in Ariel—to demonstrate the manner in which businesses finance, develop and profit from the illegal settlement housing market on lands seized from Palestinians. Many other banks and real estate agencies are active in settlements, and the focus on these companies is purely illustrative and not intended to single them out as particularly problematic.

The first case study looks at the role of an Israeli bank in the construction of a six-building complex in Ariel called Green Ariel. The bank is financing the project and provides mortgages to Israeli buyers there and elsewhere in Israeli settlements. The bank’s website advertises the pre-sale of apartments in several other buildings under construction in settlements. This is one example of the many banks that finance settlement construction or provide mortgages to settlers.

The operations of a US-based global real estate franchise is another case study illustrating business involvement in the settlement housing market. Like other real estate agencies, the branches located inside Israel offer properties for sale and rent in Ariel and other settlements; it also has a branch in the settlement of Ma’aleh Adumim.

By contributing to and benefitting from Israel’s unlawful confiscation of land, the financing, construction, leasing, lending, selling and renting operations of businesses like banks and real estate agencies help the illegal settlements in the West Bank to function as viable housing markets, enabling the government to transfer settlers there.[2] In this way, in Human Rights Watch’s view, companies involved in the settler housing market contribute to two separate violations of international humanitarian law: the prohibition on an occupying power expropriating or confiscating the resources of the occupied territory for its own benefit and the prohibition on transferring its civilians to occupied territory. By benefitting from the preferential access to land and financial incentives for doing business in the settlements, these businesses also benefit from Israel’s unlawful discrimination against Palestinians.

Israel’s confiscation of land for settlements and settlement businesses violates international law, regardless of whether the land was previously privately held, “absentee land” or so-called “state land.” Businesses operating on these unlawfully confiscated lands are inextricably tied to the ongoing abuses perpetuated by such confiscations.

While Israel maintains that its human rights obligations do not extend to the occupied territories, the International Court of Justice, endorsing the position of the United Nations Human Rights Committee, has refuted Israel’s position on the grounds that a state’s obligations extend to any territory under its effective control. Israel also wrongly asserts that the Fourth Geneva Convention’s prohibition on an occupying power to “deport or transfer parts of its own civilian population into the territory it occupies” does not apply to voluntary transfers. Both the plain meaning of article 49 of the Convention—which only refers to “transfer” in this clause but expressly refers to “forcible transfers” in the context of a different prohibition in the same article—and the International Committee of the Red Cross’s commentary contradict this position.

How Businesses Support the Infrastructure of Unlawful Settlements

Businesses also play a vital role in sustaining the settlements, thereby facilitating and benefitting from Israel’s violation of the international law prohibition on an occupying power transferring its civilian population into occupied territory and contributing to Israel’s discrimination against Palestinians in the West Bank. Businesses provide services of all kinds to settlers. At the same time, they contribute to the economic development of settlements by providing employment to settlers and tax revenues to settlement municipalities.

The report highlights, as an illustrative example, a company providing waste management services in Israeli settlements in the West Bank, including Ariel and the nearby Barkan industrial zone. It operates a landfill in the Jordan Valley on land that Israel confiscated in violation of the laws of occupation and helps to sustain the presence of settlements. The company also benefits from Israel’s discriminatory approval requirements that favor Israeli companies servicing settlements but discriminate against Palestinian companies servicing Palestinians. In 2004, Israel invested in upgrading the facility in the Jordan Valley and the Civil Administration gave it a permit to operate there, even though the site currently exclusively services Israeli and settlement waste.

Meanwhile Palestinians have struggled to obtain funding and permits for landfills. All authorized landfills servicing Palestinians are funded by international donors. In one case, Israel has refused to retroactively approve a Palestinian site, and in another, it forces a Palestinian landfill site to accept waste from settlements established in violation of international law.

More generally, settlement businesses provide employment to settlers, which is a key to attracting and maintaining settlers. Around 55,440 settlers—about 42 percent of the settlement workforce—are employed in public or private sector jobs in Israel’s settlements. Settlement businesses also pay taxes to settlement municipalities, thus contributing to the sustenance of the settlements. Although the tax rates are often lower than rates inside Israel, they still make up a sizable share of the municipality’s income.

For example, the 2014 projected budget of the settlement of Barkan, which is associated with the industrial zone of the same name, anticipated that around 6 percent of its budget—350,000 shekels of a six million shekels ($87,500 of $1,500,000) budget—would come from corporate taxes, and that Barkan would take in another nearly million shekels ($250,000) in water taxes, a portion of which factories in the industrial zone would pay. In 2014, the subsidiary of a European cement company that owns a quarry in the West Bank paid €430,000 ($479,000) in taxes to the Samaria Regional Council for its operation of the Nahal Raba quarry.[3]

Without the participation and support of such private businesses that service Israel’s settlements, the Israeli government would incur much greater expenses to sustain the settlements and their residents. In this way, businesses contribute to Israel’s maintenance and expansion of unlawful settlements.

How Businesses Contribute to and Benefit from Labor Abuse

While all settlement-related business activity runs afoul of international standards on the human rights responsibilities of businesses, regardless of labor conditions, the lack of clear labor protections for Palestinians working in settlements creates a high risk of discriminatory treatment and other abuses. As noted, Israeli courts apply Israeli civil law to settlers, while Palestinians are subject to Jordanian law as it existed at the start of the occupation in 1967, except as amended by military order. In 2007, Israel’s Supreme Court ruled that, in the case of labor laws, this two-track legal system is discriminatory, and Israeli law should govern employment conditions of Palestinians in settlements, giving Palestinian employees the right to sue their employers in Israeli courts for violations of Israeli labor laws. But the government has not implemented this ruling, and claims it cannot investigate and enforce compliance with these laws.

The virtually complete lack of government oversight, as well as Palestinian workers’ dependency on Israeli-issued work permits, creates an enabling environment for settler employers to pay Palestinian workers below Israel’s minimum wage and deny them the benefits they provide to Israeli employees. Notwithstanding the international humanitarian law prohibition against applying Israeli law to occupied territory, Israel is obliged by international human rights law to ensure that all civilians under its effective control enjoy all human rights without discrimination according to ethnicity, citizenship, or national origin and therefore must bring conditions for Palestinian workers in settlements in line with those of settlers.

According to the workers’ rights group Kav LaOved, at least half of settlement companies pay Palestinian workers less than Israel’s minimum hourly wage of 23 shekels ($5.75), with most of these workers receiving eight to 16 shekels per hour ($2 to $4), no vacation, sick days, or other social benefits, and no pay slips. Human Rights Watch spoke to one worker, Hani A. (pseudonym), who is employed in a factory in Barkan that produces Hanukah candles and plastic containers. He said he works 12-hour night shifts, receives only one half-hour break, and earns 8.5 shekels ($2.12) per hour. Another person, Mujahid, who worked in Barkan until September 2014, told Human Rights Watch he earned 16 shekels ($4) per hour and worked between 12 and 15 hours a day. He recalled one week during which he worked from 3 a.m. to 8 p.m.

The report highlights the illustrative case of a textile manufacturer in Barkan that supplied linens to an upscale American home goods chain. In 2008, 43 employees, almost half of whom were women, sued the exporter, alleging they were earning hourly wages of 6 to 10 shekels ($1.50 to 2.50) and receiving no social benefits; women workers alleged they were receiving around 2 shekels less per hour than the men. The exporter settled all the cases out of court. The co-owner of the business claims that all employees currently receive minimum wage and full benefits under Israeli law. The exporter moved its facilities from the occupied territories in October 2015.

Supporters of settlement businesses have argued that they benefit Palestinians by providing them with employment opportunities and paying wages that exceed wages for comparable jobs in areas where Israel has ceded limited jurisdiction to the Palestinian Authority. They have raised concerns that, in some cases, ceasing Israeli business activity in settlements may force the layoff of Palestinian workers. Some have even described settlement businesses as models of co-existence or an alternative path to peace through economic cooperation.

The employment of Palestinians in settlement businesses does not, in any case, remedy settlement businesses’ contribution to violations of international human rights and humanitarian law. The cumulative impact of Israeli discrimination, as documented in this report and numerous others, is to entrench a system that contributes to the impoverishment of many Palestinian residents of the West Bank while directly benefitting settlement businesses, making Palestinians’ desperate need for jobs a poor basis to justify continued complicity in that discrimination.

The World Bank estimates that discriminatory Israeli restrictions in Area C of the West Bank, most of which are directly linked to Israel’s settlement and land policies, cost the Palestinian economy $3.4 billion a year. These restrictions drive up unemployment and drive down wages in areas of the West Bank. Farmers in Area C are particularly hard hit by Israel’s unlawful and discriminatory land and water policies, causing many to lose their traditional livelihoods. Many Palestinians are therefore left with little choice but to seek employment in settlements, providing a steady source of cheap labor for settlement companies.

The head of the village council of Marda, an agricultural village which lost much of its land to Ariel, told Human Rights Watch: “We used to have 10,000 animals, now you can barely find 100, because there is nowhere for them to graze. So the economy collapsed and unemployment increased.” As a result, many of the villagers now have little choice but to work in settlements, he said.

******

As noted, many of the violations documented in this report under the four headings listed above are intrinsic to long-standing Israeli policies and practices in the West Bank. Companies operating in or with settlements cannot mitigate or avoid contributing to these abuses through their own operations. For this reason, Human Rights Watch recommends that, absent a radical shift in Israeli policies and practices that would allow businesses to operate in accordance with their responsibilities under international law, businesses should cease settlement-related activities, including operating in settlements or financing, administering or otherwise supporting settlements or settlement-related activities and infrastructure.

The UN Guiding Principles provide that enterprises should undertake human rights due diligence to identify and mitigate the adverse human rights impact not only of their own activities but also activities to which they are directly linked by their business relationships. In the latter case, businesses should ensure that their supply chains are not tainted by serious abuses. A business would not necessarily be expected to completely sever all its relationships with another actor that is operating in the settlements, but it would need to ensure that its relationships are not themselves contributing to or otherwise inextricably bound up with serious abuses.

Moreover, states have certain obligations given the nature of Israel’s violations in the West Bank. The Fourth Geneva Convention requires states to ensure respect for the Convention, and they therefore cannot recognize Israeli sovereignty over the occupied Palestinian territories or render aid or assistance to its unlawful activities there. In an advisory opinion, the International Court of Justice found that states also have such obligations because Israel’s settlement regime—as well as the separation barrier, the main focus of the opinion—violate international laws that are erga omnes, meaning that all states have an interest in their protection.

As a result, Human Rights Watch recommends that states review their trade with settlements to ensure they are consistent with their duty not to recognize Israeli sovereignty over the occupied Palestinian territories. For example, states should require and enforce clear origin labeling on settlement goods, exclude such goods from receiving preferential tariff treatment reserved for Israeli products, and not recognize or rely on any certification (such as organic or health and safety) of settlement goods by Israeli government authorities unlawfully exercising jurisdiction in the occupied territories.

In addition to states’ obligations under international humanitarian law, the UN Guiding Principles call on states to respect the principles and develop guidelines to implement them. A number of states are currently developing national action plans for this purpose. States should provide guidance to companies operating in conflict-affected areas, including in situations of military occupation such as the occupied Palestinian territories.

Recommendations

To Businesses Active in Israeli Settlements

- Cease activities carried out inside settlements, such as building housing units or infrastructure, the extraction of non-renewable resources, or providing waste removal and landfill services.

- Avoid financing, administering or otherwise supporting settlements or settlement-related activities and infrastructure, such as through contracting to purchase settlement-manufactured goods or agricultural produce, to ensure the businesses are not indirectly contributing to and benefiting from such activities.

- Conduct human rights due diligence to ensure that supply chains do not include goods produced in settlements.

To Israel

- Abide by Israel’s obligations as the occupying power and dismantle settlements, including industrial zones and business operations, in the occupied West Bank, including East Jerusalem.

- Lift unlawful and discriminatory restrictions on Palestinians in occupied territory that contribute to Palestinian poverty and unemployment, including restrictions on Palestinian land and development and extraction of natural resources. End any policies on the operations of business in the occupied territories that violate international humanitarian or human rights law, including those that permit the extraction of natural resources when this does not benefit the population of the occupied territory or is not strictly required by military necessity.

- Cease providing financial incentives, including subsidies for development costs in settlements and lower tax rates, to Israeli and international businesses located in the occupied West Bank.

- Cease registering the establishment or permitting the operation of Israeli or international businesses in the occupied West Bank unless the purpose of the operations is to benefit the Palestinian people and is consistent with international humanitarian law.

To Third-Party States

- Assess trade with settlements and adopt policies to ensure such trade is consistent with states’ duty not to recognize Israeli sovereignty over the occupied Palestinian territories. This includes requiring exporters to accurately label goods produced in settlements as such, excluding such goods from preferential treatment under Free Trade Agreements with Israel, and refraining from recognizing the Israeli government’s authority to certify the conditions of production of settlement goods (such as compliance with organic or other criteria).

- Avoid offsetting the costs of Israeli government expenditures on settlements by withholding funding given to the Israeli government in an amount equivalent to its expenditures on settlements and related infrastructure in the West Bank.

- Provide guidance on implementing the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights to companies operating in conflict-affected areas, including in the context of military occupations such as the occupied Palestinian territories.

Methodology

This report examines Israeli and international companies engaged in activities related to Israeli settlements and the ways in which they contribute to and benefit from Israel’s violations of international humanitarian and human rights law in the occupied West Bank. The scope of the report does not include the Golan Heights, although some of the analysis may be applicable there, nor does it include the Gaza Strip, since Israel removed its settlements from there in 2005.

The five case studies of companies selected for this report highlight the wide range of business involvement in Israeli settlements, and the range of international legal prohibitions and human rights abuses implicated in each sector examined. The case studies are illustrative of the more general problem–none imply that the businesses described are the most problematic cases.

In researching this report Human Rights Watch reviewed court decisions; data provided by the Civil Administration, Palestinian Authority officials, and non-governmental organizations; Israeli state comptroller reports; transcripts of Knesset committee meetings; and other documents.

Human Rights Watch interviewed 20 Palestinians whose land was confiscated, expropriated or subject to significant restrictions due to settlements and related infrastructure; 25 Palestinians who previously worked or currently work in Israeli settlements; and eight Palestinian businessmen. Human Rights Watch also interviewed two Israeli lawyers and two Palestinian lawyers specialized in issues related to Palestinian employment in settlements, and an additional Palestinian lawyer specialized in land cases. An Arabic translator facilitated many of the interviews with Palestinians. Human Rights Watch consulted broadly with Palestinian and Israeli trade unions and workers’ rights and human rights organizations.

All interviewees freely consented to be interviewed and Human Rights Watch explained to them the purpose of the interview, how the information gathered would be used, and did not offer any remuneration. In some cases interviewees requested to remain anonymous or to be identified only by their first names and first initial. The report indicates where pseudonyms are used.

Human Rights Watch held some of the interviews with Palestinians in small group settings, including one larger group of seven farmers who own land Israel confiscated or made subject to restrictions. Researchers sought responses to questions about each case from the relevant companies, as well as the Civil Administration. Wherever possible, we took information about settlements from Israeli government sources. Human Rights Watch staff conducted field research for three weeks in December 2014 and ten days in March 2015.

Human Rights Watch wrote letters to all companies that appear as case studies in the report, as well as Israel’s Civil Administration, sharing its preliminary findings and requesting relevant information. Two companies, Heidelberg Cement and a textile manufacturer, responded in writing; their responses are reflected in the report and are reproduced in the annex, unedited apart for the redaction of certain names. Human Rights Watch also met with a co-owner of the textile manufacturer and had a number of phone conversations with a representative of an American retailer that sources from the manufacturer; these conversations are reflected in the report. No other companies responded.

Note on currency conversion: this report used an exchange rate of 4 New Israeli Shekels (NIS) and .90 euros per US dollar.

I. The Problematic Human Rights Impact of Settlement Businesses

In the immediate aftermath of Israel’s occupation of the West Bank in June 1967, Israeli civilians, supported by the Israeli government and protected by Israeli security forces, began moving across Israel’s eastern border to “settle” the land in order to claim it as part of “the Jewish state.”[4] Today, the Israeli civilian presence has grown into a network of more than half a million settlers living in 137 settlements officially recognized by the Ministry of Interior, and more than 100 settlement outposts, which are unauthorized but still receive substantial state support.[5] The population of settlements grew 23 percent from 2009 to 2014, far outpacing growth of less than 10 percent in Israel overall.[6]

These virtually exclusively Jewish cities, towns, and villages are, for the most part, seamlessly assimilated into Israel’s infrastructure and economy, such that they appear almost indistinguishable from Israel.[7] In 1967, Israel also directly annexed East Jerusalem, a 72 square kilometer area of the West Bank. This area remains occupied territory under international humanitarian law.[8]

Israeli settlements, including in East Jerusalem, violate Israel’s international humanitarian law obligations and are a central feature of Israeli policies that dispossess, discriminate against, and forcibly displace Palestinians in violation of their human rights.[9] While the Israeli government is responsible for the unlawful and discriminatory policies that enable and encourage settlement expansion, private actors, including Israeli and international businesses across all sectors, play a critical role in developing the land that Israeli authorities appropriate into settlement cities and towns.

Israeli and international businesses choosing to locate in settlements and settlement zones, thereby becoming “settlers” themselves, make up a significant portion of Israel’s civilian presence on the ground. Israel administers approximately 20 industrial zones covering 13,650 dunams (1,365 hectares) in the West Bank, Israeli settlers oversee the cultivation of 93,000 dunams (9,300 hectares) of agricultural land, and settlement businesses operate 187 shopping centers inside of settlements as well as eleven quarries that supply around 25 percent of Israel’s gravel market.[10] The geographic footprint of Israeli commercial activity in the West Bank exceeds the built-up area of residential settlements, estimated to be about 60,000 dunams (6,000 hectares).[11] These numbers reflect the magnitude of commercial activity’s share in Israel’s civilian presence in the West Bank.

By locating in, establishing, expanding, and supporting settlements, businesses contribute to Israel’s rights violations. Such businesses depend on and contribute to Israel’s unlawful confiscation of Palestinian land and other resources, and facilitate the functioning and growth of settlements. The businesses also benefit from these violations, as well as Israel’s discriminatory policies that privilege settlements at the expense of Palestinians, such as by profiting from access to unlawfully confiscated Palestinian land and water, government subsidies, and Israeli-issued permits for developing land that Israel severely restricts for Palestinians.

This report describes two types of businesses engaged in settlement activity to show how businesses across a range of sectors with varying involvement in settlements contribute to rights abuses.

The first type of settlement business includes companies that manage the practical demands of constructing and maintaining settlements. Three of the report’s case studies fall into this type: a bank that finances and provides mortgages for settlement homes, a real estate franchise that sells them, and a waste management company that processes settlement trash. The direct contribution these companies make to Israel’s unlawful settlement regime is self-evident. As is discussed in more detail below in the chapter on legal obligations, the transfer of civilians, directly or indirectly, by the occupying power into the occupied territory is a war crime. Many such businesses also locate in settlements and depend on land and other resources that Israel unlawfully confiscated from Palestinians, thereby contributing to additional rights violations. Israeli settlements in the West Bank also entrench and benefit from Israel’s human rights abuses against Palestinian residents in the West Bank. This is also discussed in more detail below in the chapter on discrimination.

The second type of settlement business includes companies that engage in activities that do not directly provide services to residential settlements, yet nonetheless are based in settlements or settlement industrial zones. These businesses, which may be drawn by economic reasons, such as access to cheap Palestinian labor, low rents, or favorable tax rates, constitute the most significant commercial presence in settlements.[12] They are principally manufacturers located in settlement industrial zones and agricultural producers, but this type also includes Israeli-administered companies engaged in extracting West Bank resources, such as quarries.

In Human Rights Watch’s view, such businesses also contribute to and benefit from Israel’s rights abuses. First, they support residential settlements by providing employment to settlers and paying taxes to settlement municipalities. Second, their large physical footprint and disproportionate consumption of resources substantially contribute to Israel’s unlawful confiscation of Palestinian land and natural resources. Third, settlement manufacturers and farmers benefit from Israel’s discriminatory policies and its violations of international humanitarian law–in fact, many may choose to locate in settlements to take advantage of the benefits conferred by these policies and violations.

Many settlement manufacturers and agricultural producers rely heavily on exports, such that businesses around the world become implicated in the abuses described in this report through their supply chain. These imports also implicate third-party states in a way that other kinds of settlement businesses do not, since the settlement goods pass through their borders, frequently labeled as made in Israel and benefitting from tariff agreements between the importing state and Israel.

The report includes two case studies of this second type of business. The case of a quarry highlights how settlement businesses benefit from Israeli policies that discriminate against Palestinians. The case of a textile manufacturer examines labor conditions for Palestinians working in settlement businesses. Because of the significance of settlement industrial zones and agriculture for international businesses and third-party states, an annex to this report provides an in-depth analysis of the scale and human rights impact of these sectors.

The United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights provide that enterprises should undertake human rights due diligence to identify and mitigate the human rights harm not only of their own activities but also activities to which they are directly linked by their business relationships. Businesses should ensure that their relationships with other businesses, including those in their supply chain, are not tainted by abuses.

Many of the violations and abuses that companies operating in or with the settlements facilitate or benefit from are intrinsic to long-standing Israeli policies and practices in the West Bank and therefore beyond the control of companies to avoid or mitigate. For this reason, Human Rights Watch recommends that businesses cease settlement-related activities.

Businesses should not locate in settlements, or provide financing, services, or other support to settlements; they should also cease trading with settlement businesses. A business would not necessarily be expected to completely sever all its relationships with another actor that is operating in the settlements, but it would need to ensure that its relationships are not themselves contributing to or otherwise inextricably bound up with serious abuses.

Moreover, states have certain obligations given the nature of Israel’s violations in the West Bank. The Fourth Geneva Convention requires states to ensure respect for the Convention, and they therefore cannot recognize Israeli sovereignty over the occupied Palestinian territories or render aid or assistance to its unlawful activities there. In an advisory opinion, the International Court of Justice found that states also have such obligations because Israel’s settlement regime—as well as its separation barrier, the main focus of the opinion—violate international laws that are erga omnes, meaning that all states have an interest in their protection.

As a result, Human Rights Watch recommends that states review their trade with settlements to ensure they are consistent with their duty not to recognize Israeli sovereignty over the occupied Palestinian territories. For example, states should require and enforce clear origin labeling on settlement goods, exclude such goods from receiving preferential tariff treatment reserved for Israeli products, and not recognize or rely on any certification (such as organic or health and safety) of settlement goods by Israeli government authorities unlawfully exercising jurisdiction in the occupied territories.

II. International Legal Obligations

International Humanitarian Law

Settlements violate Article 49 of the Fourth Geneva Convention, which governs occupied territories: “The occupying Power shall not deport or transfer parts of its own civilian population into the territory it occupies.”[13] The Fourth Geneva Convention also prohibits individual or mass forcible transfers of protected persons in an occupied territory, or their deportation from that territory.[14] In 2004, the International Court of Justice, citing the Fourth Geneva Convention and other sources of international law, affirmed that “the Israeli settlements in the Occupied Palestinian Territory (including East Jerusalem) have been established in breach of international law.”[15]

The Rome Statute, the treaty establishing the International Criminal Court (ICC), includes among its list of war crimes within the Court’s jurisdiction “[t]he transfer, directly or indirectly, by the Occupying Power of parts of its own civilian population into the territory it occupies, or the deportation or transfer of all or parts of the population of the occupied territory within or outside this territory.”[16] Although Israel is not a member of the ICC, Palestine acceded to the Rome Statute on January 2, 2015, which entered into force April 1, 2015 for the territory of the State of Palestine. The Palestinian government lodged a declaration giving the court a mandate to investigate crimes committed in or from Palestine back to June 13, 2014. The United Nations General Assembly accorded Palestine non-member observer state status in 2012, allowing it to become a party to international conventions, but this does not change the legal status of the occupation.

In almost all cases, settlements entail an additional international humanitarian law violation: Israel’s confiscation of Palestinian land and other resources in violation of the Hague Regulations of 1907.[17] Article 55 of the Hague Regulations makes public resources in occupied territory, including land, subject to the rules of usufruct. A generally accepted legal interpretation of these rules is that “the occupying power can only dispose of the resources of the occupied territory to the extent necessary for the current administration of the territory and to meet the essential needs of the [occupied] population.”[18] According to the Israeli legal scholar Eyal Benvenisti, “there is little doubt today that this condition is binding on all uses of immovable public property.”[19]

Private property is subject to more stringent protection under international humanitarian law. The Hague Regulations state that “Private property cannot be confiscated” and the Fourth Geneva Convention prohibits the destruction of private property unless “absolutely necessary” for military purposes.[20]

Human Rights

International human rights law has long established the basic principles of non-discrimination and equality.[21] Discrimination is where laws, policies or practices treat persons in similar situations differently due to, among other criteria, race, ethnic background or religion, without adequate justification. States are obliged not to take any step that “has the purpose or effect of nullifying or impairing the recognition, enjoyment or exercise, on an equal footing, of human rights and fundamental freedoms” based on race, color, descent, or national or ethnic origin.[22] The prohibition against racial discrimination is considered one of the most basic in international human rights law–the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights states specifically that even in times of public emergencies, measures taken by states to derogate from other rights obligations must not “involve discrimination solely on the grounds of race … or religion.”

While Israel maintains that its human rights obligations do not extend to the occupied territories, the United Nations Human Rights Committee, the body charged with interpreting and enforcing the ICCPR, has repeatedly found that “the provisions of the Covenant apply to the benefit of the population of the occupied territories.”[23] The International Court of Justice endorsed this view in its Advisory Opinion regarding Israel’s separation barrier: the ICCPR “is applicable in respect of acts done by a State in the exercise of its jurisdiction outside its own territory.”[24]

With regard to the treatment of employees, the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights specify that corporations have a responsibility to respect domestic law, in addition to, at a minimum, rights set out in the International Labour Organization’s Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work. These fundamental principles include a prohibition on discrimination, defined as the disparate and worse treatment of members of a group based on prohibited grounds such as ethnicity or national origin. Companies are expected to undertake effective due diligence measures to help ensure that they do not engage in discrimination themselves.[25] Due diligence should also endeavor to ensure that other entities including a company’s suppliers and partners do not engage in discrimination that is directly linked to the company’s business operations, products or services by their business relationships.[26]

Israel’s “two-track” legal system in the West Bank, which applies a combination of Jordanian law and Israeli military orders to Palestinians and Israeli law to Israelis, violates the human rights prohibition on discrimination. Notwithstanding the international humanitarian law prohibition on Israel extending its domestic laws and enforcement authority to the occupied territories as though it were the sovereign there, international human rights law nonetheless requires Israel to avoid discrimination between Israeli settlers and Palestinian residents of the West Bank—or, in the words of the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, “to ensure that all civilians under its effective control enjoy all humanrightswithout discrimination based on ethnicity, citizenship, or national origin.”[27]As the Committee noted, Israel denies that its human rights obligations extend to occupied territory,but went on to say that that position is inconsistent with the extended nature of the occupation.[28]

Both international humanitarian and human rights law strictly restrict a state’s right to forcibly transfer or displace people from one area to another. The Fourth Geneva Convention permits a state to evacuate civilians only for their own security or for “imperative military reasons,” and in that case the state must provide the displaced people with accommodation “to the greatest practicable extent” and allow their return to their homes as soon as possible.[29] The prohibition of forcible transfer extends beyond cases where a military force directly and physically relocates a population under its control, to cases where the military force renders life so difficult for the population that they are essentially forced to leave.[30] The ICTY Appeals Chamber has held that “forcible transfer” is “not to be limited to [cases of the use of] physical force” but that “factors other than force itself may render an act involuntary, such as taking advantage of coercive circumstances.”[31]

The International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), which Israel ratified in 1991, requires the Israeli authorities to respect the right to adequate housing. The Committeeresponsible for interpreting the ICESCRhas made clear that the right to adequate housing includes protection from involuntary removal from one’s home by the state (known as “forced eviction” under human rights law) unless the state can show it is a reasonable and proportionate step that complies with other human rights principles.

Furthermore, in human rights jurisprudence on the right to property or possessions, regional courts, including the European and Inter-American Courts of Human Rights, have concluded that states should recognize as property, individual, family and group traditional use and occupation of buildings and lands, even where such property rights have not been formally recognized in property registries but where the occupier has been treated as having property rights for a long period of time. All property rights can be interfered with only when there is clear domestic law, the interference is for a legitimate aim, the interference is the least restrictive possible, and adequate compensation is paid. Permanent seizure or destruction of property can be justified only where no other methods are possible and compensation is paid.

Business and Third-Party State Obligations

Although governments have primary responsibility for promoting and ensuring respect for human rights, businesses also have a responsibility to avoid causing or contributing to human rights abuses. Companies have a responsibility to identify and mitigate potential human rights problems linked to their operations, and to ensure that victims of such abuses have access to an appropriate remedy. Human Rights Watch opposes business operations that cause, facilitate, exacerbate or contribute to serious human rights abuses or international humanitarian law violations, unless those business operations are able to either eliminate that connection or ensure that the abuses or violations at issue are substantially mitigated or remedied.[32]

This principle is reflected in the United Nations “Protect, Respect, and Remedy” Framework and the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, which are widely accepted by companies and governments.Under the Guiding Principles, companies have a responsibility to “avoid causing or contributing to adverse human rights impacts through their own activities,” as well as to “seek to prevent or mitigate adverse human rights impacts that are directly linked to their operations, products or services by their business relationships,even if they have not contributed to those impacts.” Companies are expected to undertake adequate due diligence to identify the potential adverse human rights impact arising from their activities and that of their suppliers, and to help ensure that victims have access to adequate remedies for any abuses that occur in spite of these efforts. Companies should refrain from doing business where serious adverse human rights impacts are unavoidable.

Moreover, settlement businesses profiting from land and resources that Israel unlawfully appropriated from Palestinians may violate an international law prohibition–which also exists in many domestic legal systems–against an individual or company knowingly benefitting from the fruits of illegal activity. This principle is enshrined in Article 6 of the United Nations Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime, which prohibits “the acquisition, possession or use of property, knowing, at the time of receipt, that such property is the proceeds of crime.” In his report on businesses profiting from Israeli settlements, the UN Special Rapporteur on the Situation of Human Rights in Palestinian Territories Occupied Since 1967 also analyzed such businesses’ responsibilities under international criminal law and found that businesses that play a causal role to Israel’s transfer of its citizens to settlements “in certain instances may be enough to make them accomplices of that crime.”[33]

Third-party states also have obligations under international humanitarian law. Article 1 of the Fourth Geneva Convention provides that: “The High Contracting Parties undertake to respect and to ensure respect for the present Convention in all circumstances.” At a minimum, this creates an obligation for states not to act contrary to the Convention, and thus prohibits states from recognizing Israel’s sovereignty over the territory it occupies.

The International Court of Justice, in an advisory opinion regarding the legality of the separation barrier that Israel constructed in the West Bank, found that Israel’s settlement regime violates obligations under international humanitarian law “which are essentially of an erga omnes character,” meaning they apply to all states, and all states have a legal interest in their protection.[34] On this basis, as well as states’ duty to ensure respect for the provisions of the Fourth Geneva Convention, the court concludes: “[A]ll states therefore are under an obligation not to recognize the illegal situation resulting from the construction of the wall in Occupied Palestinian Territory, including in and around East Jerusalem. They are also under an obligation, not to render aid or assistance in maintaining the situation created by such construction.”[35] Although the focus of the case was the separation barrier that Israel constructed around settlements rather than the settlements themselves, the court affirmed that the illegality of settlements under international law and so the applicability of the same obligation not to recognize the unlawful situation resulting from Israel’s settlements, or to aid or assist Israel’s violations.[36]

III. How Businesses Contribute to and Benefit from Discrimination

Businesses contribute to and benefit from the two-tiered system of laws, rules, and services that Israel operates in the parts of the West Bank that are under its exclusive control, which provides preferential services, development, and benefits for Jewish settlers while imposing harsh conditions on Palestinians. Settlement companies contribute to Israel’s discriminatory policies by facilitating the presence of settlements, but they also directly benefit from discriminatory economic policies that, on the one hand, encourage settlement business by, for example, providing subsidies and low tax rates, while on the other hand stifle Palestinian businesses and the Palestinian economy by imposing discriminatory restrictions on them.

The 1995 Oslo interim agreement gave Israel exclusive control over what the agreement called Area C, which covers 60 percent of the West Bank, while it ceded some control to the newly established Palestinian Authority in Areas A and B. Area C, which is the only contiguous area of the three areas in the West Bank, contains all Israeli settlements and substantial amounts of the West Bank’s water sources, grazing and agricultural land, and the land reserves required for developing cities, towns, and infrastructure.[37] Areas A and B are made up of 227 cantons that include most Palestinian towns and cities. The interim agreement was intended as a temporary stage in preparation for Palestinian statehood within five years, but it still remains in effect, and Israel maintains full administrative and military control over Area C.[38]

A 2010 Human Rights Watch report, Separate and Unequal, documented Israel’s discriminatory laws and practices that favor settlers at the expense of Palestinians in Area C. It highlighted four major areas of discrimination—construction, zoning, and demolitions; freedom of movement; water; and land confiscation—the only discernable purposes of which appear to be promoting life in the settlements while in many instances stifling growth in Palestinian communities and even forcibly displacing Palestinian residents.[39]

The discriminatory nature of Israel’s settlement regime is not an incidental shortcoming but rather one of the occupation’s central features. In fact, according to the International Committee of the Red Cross’s 1958 commentary on the Geneva Convention, the convention’s drafters chose to prohibit an occupying power from transferring its citizens into occupied territory because of its close link with discrimination and economic harm against the local population: “Certain Powers,” it notes, “transferred portions of their own population to occupied territory for political or racial reasons or in order, as they claimed, to colonize these territories. Such transfers worsened the economic situation of the native population and endangered their separate existence as a race.”[40]

Encouraging Settlement Business: Government Financial Incentives

Successive Israeli government have actively encouraged the migration of Israeli and international businesses to settlements by offering a variety of financial incentives that they do not provide to Palestinian businesses in areas of the West Bank under its control. A significant channel of government support is its categorization of most Jewish settlements and almost all settlement industrial zones as National Priority Areas (NPAs), a classification also reserved for areas within Israel facing economic hardship or located near a border.[41] The government also provides support by investing in public infrastructure projects to help draw businesses to the area.

NPAs are eligible for a series of financial benefits, which, according to the Ministry of Construction, have four aims: “(1) to alleviate housing shortages affecting many residents of Israel; (2) to encourage positive migration to these communities; (3) to encourage development in these communities; and (4) to improve the economic resilience of these communities.”[42] From 1998 until 2002, Israel categorized all settlements as NPAs.[43] The government drew a new map of NPAs in 2002 that included 104 settlements, but Adalah, an Israeli civil rights group, challenged it on grounds of discrimination, since only four of the 553 communities designated as NPAs were Arab (all inside of Israel).[44] In 2006, the Supreme Court found that the map discriminated against Arab communities in Israel and ordered the government to come up with a new map within one year. Seven years after the court ordered it to do so, the government approved a revised map of NPAs, accepted by the court, which includes 90 settlements. Almost all settlement industrial zones are NPAs, as are 23 settlements in the Jordan Valley and the Dead Sea region, where most settlement agriculture is located.[45]

For NPA settlements, government benefits include reductions in the price of land, preferential loans and grants for purchasing homes, grants for investors and for the development of infrastructure for industrial zones, indemnification for loss of income resulting from custom duties imposed by European Union countries, and reductions in income tax for individuals and companies.[46]

In “urban” NPAs, which is the classification of most settlement NPAs, the government may subsidize up to 50 percent of development costs, up to 107,000 shekels (US$26,750) per housing unit, depending on the topography of the area.[47] In “rural” NPAs, which include agricultural settlements in the Jordan Valley, the government may subsidize up to 70 percent of development costs, with a maximum of 150,000 shekels ($37,500) per housing unit, again depending on topography.[48] First-time home purchasers in NPAs also benefit from subsidized mortgages and a beneficial mortgage interest rate of 4.5 percent. Many of these subsidies—such as for development and commercial infrastructure—directly benefit businesses located in settlements. In 2013, for example, the government gave development grants of 2.17 million shekels ($543,000) to a furniture company in Barkan and 937,000 shekels ($234,000) to a plastics factory there.[49]

Furthermore, companies in NPAs that qualify for “approved enterprise” status are eligible for special benefits from the Ministry of Economy over and above what they would otherwise receive. Approved factories can benefit from two potential packages: direct grants and national tax benefits.[50] The first track offers companies 20 percent subsidies for any investment in real property. Alternatively, the tax track offers a reduced corporate tax rate of 6 percent in some NPAs (as opposed to 12 percent tax in other areas), beginning in 2015.[51]

Israel also encourages businesses to move to settlements by investing in public infrastructure to support them. Policy statements from the years during which Israel was first developing the settlement economy reveal that Israel intentionally provided settlement companies with financial incentives, including by designating settlements as NPAs and investing in necessary infrastructure, in order to encourage them to locate in the West Bank. In a 1982 Knesset meeting, Gideon Patt, Minister of Industry and Trade, said that his ministry had established six industrial zones in the occupied territories, in addition to small industrial buildings. “And we’re also pushing factories there,” he said. “They don’t fall from the sky. They come from encouragement.”[52]

Two years later Minister Patt spelled out what kinds of encouragement his ministry offers. He reported that the government succeeded in bringing 300 factories to seven newly established settlement industrial zones by building necessary infrastructure and by classifying these areas as NPAs, and designating some of the factories there as “approved enterprises,” thereby making them eligible for generous financial incentives. He also said his ministry was working to establish both regional industrial centers to serve centrally located settlements and industries linked to small settlements, “considering the employment needs of those communities.”[53]

Settlement agriculture businesses benefit from another type of economic incentive: the apparently deliberate failure of the government to collect land fees owed to it. According to the state comptroller’s report in 2013, the Civil Administration does not enforce a law requiring settlements to pay it leasing fees for 83 rural settlements on so-called “state land,” resulting in a loss of 50 million shekels ($12.5 million) each year.[54] In the words of the comptroller: “this is a fundamental failure on the part of all the parties involvedthat has persisted for many years.” As far back as 2005, the Civil Administration acknowledged the issue and attributed it to a lack of manpower, yet, to date, the Israeli government has not allocated additional resources to collect leasing fees. In 2011, the Finance Ministry finally decided to establish a collection unit, but it appears that it has yet to implement this decision.[55]

Stifling Palestinian Businesses and Economy: Discriminatory Restrictions

In contrast to settlements and settlement businesses, none of the Palestinian areas in Area C is eligible for National Priority Area (NPA) status despite being poorer and less developed than settlements. Nor do they receive most other basic government services that Israel provides to settlements, regardless of their NPA status. Many Palestinian communities in Area C rely on international funding to provide basic infrastructure, such as solar panels, schools, and water tanks.[56] In fact, Israel’s policies of severely restricting Palestinian access to building permits and restricting farmers access to their land, described in more detail below, has the cumulative impact of forcing many Palestinians to leave Area C.[57]

Some of these Israeli policies also violate international humanitarian law related to land confiscation; construction permits, zoning and demolitions; water; and freedom of movement.[58] These and other policies not only undermine Palestinian economic development, but also give a clear economic advantage to settlement companies compared to Palestinian companies.

One of the principal methods Israel uses to restrict Palestinian development is its refusal in almost all cases to grant Palestinians permits to build on or develop land or to extract resources.[59] The World Bank estimates that if Israel lifted administrative restrictions, such as on construction and resource extraction in Area C, it could generate $3.4 billion annually for the Palestinian economy, an increase of 35 percent in its GDP. The additional revenues would generate $800 million in government tax receipts, equal to half the Palestinian Authority’s debt.[60] Instead, Israel refuses to issue any Palestinians a permit to harvest minerals such as potash and bromine from the Dead Sea, amounting to a nearly $1 billion loss annually.[61] Israel also restricts Palestinian access to large areas of land it designates as settlement municipal areas, firing zones, or nature preserves, and strictly limits the amount of water it allocates to Palestinians, which the World Bank estimates costs the agricultural sector $704 million annually.[62] A report by a group of Israeli, Palestinian, and international economists found that if an additional 100,000 dunams (10,000 hectares) of land were available for Palestinian development in the Jordan Valley, it could create between 150,000 and 200,000 jobs.[63]

Many Israeli policies that harm Palestinian businesses and the Palestinian economy are directly related to settlements. Israel has designated 70 percent of Area C for settlement regional councils (which are off-limits to Palestinian construction) and has approved master plans for Jewish settlements covering 26 percent of Area C.[64] Israel also builds settlement infrastructure, such as roads, checkpoints, and the separation barrier, on expropriated Palestinian land, that at times increases Palestinian transportation delays and costs.[65]

Furthermore, Israel has developed building plans for Palestinians on only 1 percent of Area C, most of which has already been built up, and on this basis Israel in practice rejects almost all Palestinian building-permit requests without justification. According to the Civil Administration, between 2000 and 2012, Palestinians submitted 3,565 requests for building permits. Of these only 210 were granted.[66] Israel also altered Jordanian planning laws in place in the West Bank so as to exclude Palestinians from participation in planning processes, while military orders create a separate planning track for settlers, who participate in planning their own communities.[67]

Since most of Palestine’s undeveloped lands are in Area C, Israeli land-use restrictions thwart the Palestinian construction sector and manufacturing, which requires open land for factories, and prevent Palestinians from benefitting from tourism near the Dead Sea or historical sites because they cannot build hotels, stores or other tourist infrastructure.[72]

Israeli policy and practice create economic hardship for many of the 300,000 Palestinians who live in Area C, because it is virtually impossible to obtain a permit even to build a simple shop. Palestinian structures built without a permit is much more likely to be demolished than unauthorized settlement construction, which is often retroactively authorized.[73]

The livelihoods of Palestinians in Area C are particularly affected by land restrictions since many are farmers and herders. According to a 2014 study conducted by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), 24 percent of Palestinians in Area C are farmers and 10 percent are herders, and 24 percent currently work in settlements.[74] A number of Palestinian residents of Area C told Human Rights Watch that many of those Palestinians working in settlements are farmers or herders who have lost access to their lands. In 2011, OCHA reported that families were leaving 10 of 13 communities it visited in Area C because Israeli “policies and practices implemented there make it difficult for residents to meet basic needs or maintain their presence on the land.”[75]

Palestinian public infrastructure projects, like roads, water and sewage lines, or other utilities that connect major towns or cities in Areas A and B, often must be built across Area C.[76] Therefore, the Israeli military’s denial of construction permits in areas under its control also harms Palestinians in areas under nominal Palestinian Authority control, deepening Palestinian dependence on Israeli products and services. Rawabi, a partly completed $1 billion residential and commercial project northwest of Ramallah located almost entirely in Area A, is not yet habitable because the Civil Administration delayed for years approving the required permits to connect the town to water infrastructure in Area C; in February 2015, it reportedly promised to approve the water connection.[77] The Jericho Industrial Zone in Area A has also experienced serious delays because the optimal route for a road to the zone crosses Area C, and Israeli authorities have not approved construction.[78]

Israel has exercised its control over Palestine’s borders in ways that raise the costs for Palestinian imports and exports, discriminating against and harming the Palestinian businesses in all areas of the occupied territories that engage in importing and exporting goods. Israeli authorities frequently subject imported goods destined for West Bank Palestinians to delays, resulting in additional storage and other costs.[79] Israel often requires Palestinian producers, but not Israelis, to offload and reload goods that pass through Israeli checkpoints on their way to a port for export, which adds to the expense and time required for transport.[80] Israel justifies these measures on security grounds, but they are nonetheless discriminatory since they target businesspeople solely on the basis of their national origin.

Israeli restrictions on Palestinian access to international markets also maintain Palestinian dependency on the Israeli economy. Palestinian businessman Amin Daoud, for example, said he stopped importing construction materials directly from overseas in 2012, because of unpredictable, long delays at the port and the associated storage fees.[81] Now he buys everything from Israeli importers, he said, even though this reduces his profit margin and makes his goods less competitively priced. Daoud’s situation is not unique: according to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), 39 percent of exports from Israel to the occupied Palestinian territories are imported from third countries and resold to Palestinian consumers.[82] UNCTAD estimates that this phenomenon, known as “indirect imports,” costs the Palestinian Authority US $115 million annually in lost customs duties, since Israel only transfers customs duties for goods whose original destination is the occupied Palestinian territory.[83]

Case Study: Quarrying in the West Bank

The case of quarries in the West Bank is one example of the Israeli state’s discriminatory treatment of Palestinian businesses in relation to its treatment of Israeli and international businesses. Natural stone is sometimes referred to as Palestine’s “white oil” because of the potential economic value and abundant supply of this resource.[84] According to the Palestinian Union of Stone and Marble, the industry currently provides 15,000 to 20,000 jobs and adds $250 million to Palestine’s GDP.[85] The industry is by far Palestine’s largest exporter, making up 17 percent of all exports in 2011, and reaching 60 countries.[86]

Israeli restrictions, however, keep Palestinian businesses from tapping into the full potential of this industry. Most of the quarryable land, some 20,000 dunams (2,000 hectares) with a potential value of up to $30 billion, is located in Area C.[87] According to the Palestinian Union of Stone and Marble, Israel has refused to issue any new permits to Palestinian businesses for quarrying in Area C since 1994, even though the Oslo Accords explicitly provide for Israel to consider a request for such a permit “on its merits.”[88]Because of this, as of July 2012, only nine Palestinian quarries operated “legally” in Area C with the required Israeli military permission.[89] The manager at one of these quarries told Human Rights Watch that the Civil Administration refused to renew his permit after it expired in 2012, as well as the permits of other authorized quarries.[90] Palestinian businesses that operate unauthorized quarries are vulnerable to the confiscation of their equipment, which Israel returns only after the payment of hefty fines, and other measures that greatly reduce the businesses’ economic productivity.[91]

In a clear example of discriminatory treatment, Israel’s Civil Administration has, in contrast, licensed 11 Israeli-administered quarries and crushers in the West Bank, which produce 10 to 12 million tons of stone annually.[92] The Civil Administration did not respond to a letter that Human Rights Watch sent requesting information on the justification for the difference in treatment. Furthermore, Israeli excavation of Palestinian stone for its own benefit is a violation of international humanitarian law applicable to occupation, and may amount to a war crime, as discussed in more detail below.

Article 55 of the Hague Regulations of 1907 subjects the resources of occupied territory to the laws of usufruct, which limits an occupying power to using such resources for its military needs or for the benefit of the occupied people. According to the Israeli legal scholar Eyal Benvenisti, “It is generally accepted that the occupant may not use them for its own domestic purposes.”[93] Recognizing this restriction, the occupying coalition authority in Iraq, in 2003, established the Development Fund for Iraq, which collected profits from Iraqi oil to be used for the benefit of Iraqis.[94]

In violation of this obligation, settlement quarries transfer 94 percent of their product to the Israeli market, and, according to a National Mining and Quarrying Outline plan prepared by Israel’s Ministry of Interior, it provides around one-quarter of the total consumption of quarrying materials for the Israeli economy.[95] Israel collects royalties, at a rate of approximately $1.20 per ton, from the Israeli quarry owners, and settlement municipalities collect taxes.[96] In 2009, the total royalties paid for the use of the quarries by Israeli parties was 25 million shekels ($6.25 million).[97] According to a 2015 study commissioned by the Israel Land Authority, Israel’s gravel market is heavily dependent on Israeli-owned West Bank quarries: “If not for quarry activity in the West Bank, the industry would have been mired in a crisis from a lack of supply years ago, which would have serious implications beyond the rise in prices (such as harming the ability to implement construction and/or infrastructure projects due to a lack of raw materials).”[98] This deficiency in supply could have been made up by Palestinian production, if not for of lack of access to permits and other restrictions. Data compiled by the Palestinian Union of Stone and Marble shows that, as a result of Israeli restrictions, Palestinian-owned quarries in the West Bank produce around one-quarter the amount of gravel as Israeli-administered West Bank quarries, most of which comes from a 50-year-old quarry that will soon no longer be productive.[99]